Abstract

It was hypothesized that U.S. female service members and veterans lack knowledge regarding PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder); the signs and symptoms; and treatment options. To assess the knowledge of PTSD in female U.S. service members and veterans, a 25-item questionnaire was administered to obtain baseline information. Participants then watched five videos, approximately three minutes each, provided by the National Center for PTSD. Following the videos, a post-test was administered to determine if the participants had increased knowledge of PTSD. An evaluation of the PTSD videos was completed after the post-test. Finally, a survey of intent was conducted to assess if increased knowledge of PTSD, its signs and symptoms, and its treatment options encouraged participants to seek medical care.

Chapter 1: Background and Significance

Description of PTSD, Importance to Healthcare and Stakeholders, and Description of How the Project Addressed Gaps in the Evidence

Research shows that the engagement of military service men in wars exposes the soldiers to violence making them experience trauma (Pols & Oak, 2007). The traumatic experiences portrayed by the security work force is a fundamental component which shows how nations engage in hostilities. No matter how well prepared for or battle-hardened the soldiers were before engaging in the wars, after experiencing violence and trauma, the military member can suffer deleterious effects arising from the exposure because humans simply are not mentally prepared to see that degree of trauma (Pols & Oak, 2007). Sometimes the responses to a horrific event, or the accumulation of responses to many horrific events, can lead to the on-set of PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) (Eagle & Kaminer, 2015).

According to research, the service in combat is not the only condition which leads to PTSD. Other events which trigger PSTD include sexual assault, experiencing or witnessing injury or death in training, or the care of those who experienced traumatic events (Eagle & Kaminer, 2015). If the popular literature is correct then currently the general citizenry is more aware of PTSD, or the names it was previously known as, than in any other time in history. However, the information provided by the news to the general public may be incomplete, wrong, or may perpetuate the stigma that service members and veterans with PTSD are violent (Purtle et.al. 2016).

The increased number of military members and veterans living with the disorder after decades of sustained warfare operations has contributed to the understanding of the PSTD. In addition to this increased knowledge, the United States government has allocated significant resources towards diagnosing and treating those suffering with PTSD. However, it has been realized that the U.S. Department of Defense (D.o.D) and U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) does not provide consistent treatment for service members and veterans with PTSD. Furthermore, the two departments do not measure treatment outcomes for the military members (Institute of Medicine, 2014; Zogas, 2017). Therefore, it is incumbent for all healthcare professionals to acquire accurate information about PTSD and its treatments to offer appropriate care to individuals with PTSD. Despite this general heighted awareness and increased expenditures, what does the average veteran, whether presently serving or not, know about the disorder? More narrowly, what does the average female military veteran know about it? This seems particularly important to know due to the increase in the population of women serving in the military so does the number of opportunities for ladies to help in warfare operations where violence and trauma are inherent.

A lack of knowledge about the signs and symptoms could delay recovery from PSTD. The project aims to address the gaps in the evidence because currently it appears that there is no standardized test for determining the basic knowledge level of PTSD. The project will lead to practice improvement by providing current and accurate evidence-based information about PTSD and its methods of treatment to female service members and veterans. The research was based on the PICOT question “Is an education program on the signs and symptoms of PTSD and the current approved Veterans Administration (VA) treatments for PTSD effective in increasing female service members knowledge of PTSD and current methods of treatment and ultimately enable the participants to develop self-efficacy beliefs and empowerment to advocate for oneself when it comes to one’s own healthcare?”

Purpose Statement and Aims of the Project; Questions Driving the Inquiry

The purpose and aims of this project was to determine if an educational program on PTSD that focuses on defining PTSD, the symptoms and treatment increased knowledge of PTSD among U.S. female service members and veterans. Questions driving the inquiry included:

- Do female the U.S. members of military and veterans participating in the Knowledge of PTSD Education Program score higher on the PTSD Knowledge Questionnaire after participating in the program? And a secondary question is:

- Did knowledge of PTSD acquired from the education program for female U.S. militia members and veterans encourage female members of the military and veterans to seek medical care?

Chapter 2: Review and Synthesis of Literature

Literature Search Strategy and Databases Used

Comprehensive review and literature synthesis was conducted to obtain the required information for the dissertation. The CINAHL (Cumulated Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature ), PubMed, Medline, Science Direct, Scopus, ERIC, the Social Sciences Citation Index, Science Citation Index, and SA e-Publications Service databases were used in sourcing information for the project. Moreover, before starting the project, current Theses/Dissertations on the subject were read to enhance more understanding on the topic. Besides, written materials from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Congressional reports, and information from appropriate websites were also used.

The Search terms used in the literature search included Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), U.S., female, veterans, military veterans, knowledge of PTSD, predictors of PTSD, treatments for PTSD, barriers to treatment for PTSD, PTSD and comorbidities, help-seeking, and treatment-seeking, knowledge acquisition, and the University of Wisconsin-Extension Logic Model. The literature search was further refined by searching for only full text articles, scholarly/peer reviewed/core clinical journals, English language articles, studies on humans, and articles published in the years 2007 – 2017 (Table 1: Literature Search Strategy and Databases Used).

Table 1: Literature Search Strategy and Databases Used

| Index Definitors # of Results # Kept for Review

MEDLINE PTSD, U.S., female, veterans 29,085 18

PubMed PTSD, U. S., female, veterans 144 3

CINAHL PTSD, U.S., female, veterans 285 4 ERIC Cognitive Processing Therapy 178 1

Scopus 2013 PTSD 2,189 2 2015 PTSD 2, 433 1 2017 PTSD 621 1 Science Direct PTSD, female, U.S., female, veterans, 277 3 Women service members Social Sciences Stigma Associated with PTSD 3 2 Citation Perceived Barriers to Care Among Veterans Science Citation 2010 PTSD 563 1 2011 Predictors of Health-Related Quality 12 1 Life Utilities

SA ePublications Knowledge of Traumatic Stress 1,763 1 Service

Newspaper articles U.S. Veterans 3 3 Books PTSD, female, veterans, war 11 6 combat, ethics, Costs of War Thesis/Disertation/Paper PTSD, Costs of War 3 3 Websites PTSD, female, U. S., military veterans 5 5 Essentials of doctoral education for ANP

Department of VA Women, veterans 4 4 Congressional Reports War, Healthcare, veterans 1 1

|

History of PTSD Diagnoses among Veterans

Studies shows that post-traumatic stress disorder was in existence throughout the history and was known by many different names like albeit among others. Friedman, Kean, & Resick (2014), and Eagel & Kaminer (2015) provided the historical background for PTSD becoming a medical diagnosis in its own right. Research shows that anybody can develop PTSD and thus the disorder does not affect specific people. Exposure to a traumatic event is a requirement to develop the disorder, yet only a few of those who are exposed to such an event develop PTSD (Friedman et al., 2014; Eagel & Kaminer, 2015).

Documentations on PSTD symptoms and potential remedies increased during and immediately after the wars witnessed in U.S.A and other parts of the world. During the U.S. Civil War, those who suffered from PTSD were said to have “a soldier’s heart”. In the Great War, or World War I, it garnered a more dramatic name, “shell shock”, in response to the horrific conditions endured in the trench warfare. The disorder was even more pronounced in World War II because of the exponential increase in numbers of military members and greater duration of conflict. In 1952, during the height of the Korean War, the American Psychiatric Association produced the first edition of its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (DSM-1) and referred PTSD as a “gross stress reaction” (Friedman et al., 2014). During the Vietnam Conflict, the DSM-II was published and, removed PTSD, for inexplicable reasons, as a diagnostic category.

According to Bloom, John Talbott, a psychiatrist who served in Vietnam, recognized the unique signs and symptoms of PTSD in the veterans in Vietnam and restored the diagnostic category of the disease to properly diagnose patients with the condition (Friedman et.al, 2014). Research studies on child abuse, rape, and battered women conducted in 1970s established that responses to these forms of trauma were similar to Vietnam veterans experiencing PTSD. The reactions to all traumatic events were combined into a single category in the revised DSM (Friedman et al., 2014; Eagel & Kaminer, 2015).

In 1980, the American Psychiatric Association with support from military veterans and female advocacy groups included PTSD as a certified diagnosis in its third edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) and classified the disease as an anxiety disorder with four criteria. In 1987, the American Psychiatric Association revised the DSM-III and established the six criteria for symptoms and clusters. In 1994, the American Psychiatric Association published the DSM-IV and added acute stress disorder (ASD) as a new disorder. Acute Stress Disorder (ASD) was distinguished from PTSD in that ASD symptoms last for three days to one month, whereas PTSD symptoms last for more than one month. Also, the DSM-IV Dissociative Disorders Subcommittee observed that an individual had a higher risk for developing PTSD if he or she experienced dissociative symptoms such as amnesia, depersonalization, derealization among others after a traumatic event.

The most present PTSD and ASD diagnostic criteria is in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (DSM 5). The manual categorizes PTSD together with ASD as a “trauma and stressor-related disorder” and not an “anxiety disorder.” Life-time trauma exposure is 50-60 percent in the United States adult population and Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes & Nelson (1995) reported PTSD prevalence of 7.8 percent (Eagel & Kaminer, 2015). It stands to reason that these numbers are much higher in individuals and countries exposed to war.

Recent Operations in PSTD

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) affects both male and female U. S. military members (Street et.al. 2013). The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs estimates that 11% of Afghanistan war veterans, 20 percent of Iraqi war veterans, 10 percent of Desert Storm war veterans, and 31 percent of Vietnam War veterans have post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (NIH Medline Plus, 2009). The National Center for PTSD website (2017) reported the prevalence of PTSD is 20% specifically in female troupers who carried militia operations in Afghanistan and Iraq. The U.S. military’s long-term presence in Iraq and Afghanistan has taken its toll on U.S. military personnel and their physical and mental health. The United States deployed its military to Iraq in 1990 for Operation Desert Storm and in 2002 for Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF). In 2010, the official designation of operations in Southwest Asia was changed to Operation New Dawn (OND). As of October 15, 2014, the DoD launched the U.S. and coalition campaign “Operation Inherent Resolve” (OIR) and tasked it with the responsibility of fighting against terrorist groups such as the Islamic State.

Operations in Afghanistan began in 2001 and were carried out Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) service men and women. In 2015, the name was changed to Operation Freedom’s Sentinel (OFS) and the mission was changed from combat operations to training Afghans and counterterrorism (Torreon, 2016). The unending conflicts in the Middle East have put U.S. military personnel at a greater risk for PSTD especially for those deployed to the theater of operations and those remaining at home for support roles.

Current research shows that only 1% of the American population serves in the U.S military (Sapolsky, 2015). The stressful deployment schedule of the 1% was found to be another contributing factor which increases the risk of developing PTSD among the military personnel. Evidence shows that out of the 2.5 million United States’ combat service members who previously carried military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, more than one-third have been deployed at least two or more times (Adams, 2013). The deployments have been routinely extended in addition to the security men being multiply deployed. Many service personnel have been redeployed only after being at home for a short while. Reserve and Guard personnel, unlike active duty personnel, have returned from deployments and quickly embarked to their civilian communities which has few support systems for reintegration (Haun et.al, 2016). According to research, the military peer support system needed is unavailable (Mittal, et al., 2013). The civilian communities are unable to relate what these deployed military members underwent through and mental health care is expensive and cost-prohibitive for many (Adams, 2013).

PTSD and the Role of Traumatic Stressors.

The DSM-V (2013) defined a stressor as “Any emotional, physical, social, economic, or other factor which disrupts the normal physiological, cognitive, emotional, or behavioral balance of an individual.” Furthermore, the DSM-V (2013) explained that a psychological stressor may bring on, or exacerbate, a mental disorder. A traumatic stressor can be any incident (or incidents) that may cause or threaten death, severe injury, or sexual violence to an individual, a close family member, or a close friend (DSM-5, 2013). Therefore, it is right to conclude that the severity and intensity of traumatic stressors are associated with or cause PTSD. The VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Post-Traumatic Stress by the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense, version 2.0-2010 obtained in the National Center for PTSD website categorizes the risk factors for PTSD as pre-traumatic factors, trauma-related factors, and post-traumatic factors. Pre-traumatic factors include life stresses, lack of social support, childhood trauma, pre-existing psychiatric disorder or a family history of psychiatric disorders, low levels of education, female sex, low socioeconomic status, and race (Black-American, Pacific Islander, and American Indian). Trauma-related factors consists of severe traumas such as torture, rape, and assault. Besides, the post-traumatic factors entail chronic life stresses, lack of positive social support or negative reactions from others, and loss of a loved one or resources. The guideline also provides a variety of reliable and valid PTSD screening, as well as psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy treatment options.

Diagnostic Criteria

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (2013), outlined eight criteria for PTSD, A-H, in adults, adolescents, and children older than six years and assigned the International Classification Code of 309.81 to PTSD (Figure 1. DSM-5 Criteria for PTSD).

Figure 1. DSM-5 Criteria for PTSD

| Criterion A | Experiencing a life-threatening event, adverse injury, or sexual violence which may present itself in either one or more of the following means: directly experiencing, witnessing, or learning about a traumatic event that happened to a close relative, or repeatedly experienced the traumatic event. |

| Criterion B | The individual had at least one intrusion symptom after the occurrence of the traumatic event. These signs of intrusion include recurring, instinctive, and invasive disturbing memories, dreams, and dissociative reactions or flashbacks. Powerful or lengthy psychological and physiological responses to internal or external signals symbolizing the traumatic event. |

| Criterion C | Persistently avoiding any stimuli which results to a traumatic event after the occurrence of the event, to include avoidance of thoughts and people and places that are linked to the trauma. |

| Criterion D | Negative mood and cognitive alterations related to the traumatic event, as evidenced by at least two of the following: incapacity of remembering the traumatic event aspects, negative beliefs about oneself and the world, altered thoughts concerning the source of the event leading to self-blame, persistent anxiety, dismay, irritation, guiltiness, and disgrace, decreased interest in activities, estrangement from others, inability to experience positive emotions. |

| Criterion E | Marked variations in stimulation and reactivity linked to the traumatic event by two or more of the following: irritability and anger, self-destructive behavior, hypervigilance, exaggerated startle reflex, problems with concentration that can affect the ability to keep a job, go to school, etc., and inability to sleep. |

| Criterion F | The duration of the disturbance is more than one month for Criterion B, C, D, and E. |

| Criterion G | The individual’s quality of life is affected by the disturbance to the point that it causes clinically significant distress. |

| Criterion H | The disturbance cannot be caused by substance abuse or another medical condition. |

Criterion A

For those who develop PTSD, the symptoms of the disorder usually begin to occur during the initial three months of the occurrence of traumatic incident. However, the signs and symptoms of PSTD can delay for months or years. Stimulus can be verbal, visual, auditory, or olfactory. For example, stimuli like the sound of fireworks, a car back firing, helicopters flying, or the smell blood, fuel, or something burning can trigger a negative response (Daniels & Vermetten, 2016). Also, general anesthesia for surgery can trigger post-traumatic stress years after the trauma (Berger & Scharer, 2012). Research shows that 50% of adults with PSTD recover from the symptoms of the disorder within three months, while others take several years to get well (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). According to a study conducted by the American Psychiatric Association (2013) PTSD is more prevalent in females and they show prolonged symptoms of PTSD as compared to males. PTSD is associated with increased risks of committing suicide (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Criterion B.

The PTSD symptom of intrusion impacts a service member’s and veteran’s activities of daily living. The symptom requires more research on the brain’s involvement in PTSD and deficits in inhibitory control to suppress memories. A study conducted by Catarino, Kupper, Werner-Seidler, Dalgleish & Anderson (2015) addressed Criterion B or the intrusion symptom of PTSD. Participants in the study consisted of 18 individuals diagnosed with PTSD and 18 without PTSD from a local community. The study was conducted in three phases; the study phase, think/no think (TNT) and test phase. In the study phase, participants studied 60 object-scene pairs. In the think/no-think (TNT) phase, the study directed the participants to suppress memories of the sight by surrounding an object with a red flame (no-think trial) and to remember an object that was surrounded by a green frame (think trial). In the final test phase, the study required participants to remember recalled, suppressed, and baseline items.

The study found that suppression-induced forgetting was lower in the PTSD group than in the control group. Moreover, individuals with the most adverse PTSD signs presented the highest percentage of suppression-induced forgetting. Additionally, there may be an impaired neural mechanism in individuals with PTSD. The DLPFC (right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) has to minimize hippocampus activity to suppress memories. The study conducted by Catarino, Kupper, Werner-Seidler, Dalgleish & Anderson (2015) found that individuals with PTSD had an abnormal functioning prefrontal cortex and deficient inhibitory control. Besides, the research also pointed out that people with PSTD cannot engage the DLPFC-hippocampal pathway, which causes persistent re-experiencing and ineffective suppression of memories. The PTSD symptom of intrusion impacts a veteran’s activities of daily living and requires more research on the brain’s involvement in PTSD and deficits in inhibitory control to suppress memories (Catarino et al., 2015).

Criterion D.

Bryan, Morrow, Etienne, and Ray-Sannerud (2013), reported it is the aftermath of combat, to include exposure to wounded and deceased individuals that is associated with military personnel experiencing increased rates and severity of suicide ideation. The study by Bryan, Morrow, Etienne, and Ray-Sannerud (2013) focused on guilt and shame among many other symptoms experienced by PSTD patients. Besides, the study also explored the relationship between suicide ideation with shame and guiltiness in 69 mostly active duty Air Force patients from two outpatient clinics specializing in military mental health with 23.6 percent of the patients being diagnosed with PTSD and 19.1 percent being diagnosed with major depressive disorder (Bryan et.al, 2013). Several tools were used in this study which include the Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview (SITBI) used to assess history of suicidal ideation; the Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSSI) utilized to assess current suicidal ideation; The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) used to assess depression symptom severity; the PTSD Checklist (PCL) which aided in assessing PTSD symptom severity; and the Harder Personal Feeling Questionnaire (PFQ2) for measuring guilt and shame.

The study by Bryan, Morrow, Etienne, and Ray-Sannerud (2013) aided in differentiating shame from guilt. According to theoretical conceptualizations, shame is a stable physchological condition which cannot be controlled entailing extensive individual negative evaluation in which a person feels vulnerable, superior and helpless (Bryan et.al, 2013). Conversely, theory conceptualizes guilt as a psychological condition that can be controlled usually associated with a particular behavior or action entailing a remorse or regret. Furthermore, studies point out that shame manifests itself as an intrapersonal cognitive-affective state (i.e., feeling bad about who you are), whereas guilt presents itself as an interpersonal cognitive-affective state (i.e., feeling bad about what you did to another) (Bryan et.al, 2013).

According to Bryan, Morrow, Etienne, and Ray-Sannerud (2013) study, military mental health outpatients with suicidal ideation histories report higher rates of guilt and shame. Also, the research also found that, in the patient population, guilt and shame were independently and significantly related to the adverseness of current suicidal ideation regardless of depression and PTSD severity, with guilt having a strong relation with suicidal ideation. PTSD impacts veterans’ mental health and quality of life. The guilt and shame symptoms of PSTD increases suicide ideation (Bryan et.al, 2013). It is the aftermath of combat, to include exposure to wounded and deceased individuals that is associated with military personnel experiencing increased rates and severity of suicide ideation, which ultimately leads to increased risk of veterans successfully committing suicide (Bryan et.al. 2013).

Criterion E.

Two national surveys waves were conducted by Elbogen, Johnson, Wagner, Sullivan,Taft, & Beckham, (2014) to investigate the association between PTSD and subsequent violent behavior in U.S., Afghanistan and Iraq veterans. The study supported Criterion E for PTSD. It aimed at addressing the problem of why a veteran is prone to violence which most people attribute it to hyperarousal symptoms, anger, and irritability due to PTSD. In this study 1090 female and male veterans were randomly selected from OEF/OIF veterans. In wave 1, current PTSD was measured by the Davidson Trauma Scale and current alcohol misuse was measured by the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT). In wave 2, community-based violence towards others during the one-year study period was measured as severe violence or less lethal physical aggression by using the Conflict Tactics Scale or the MacArthur Community Violence Scale. Findings revealed that PTSD has some association with violence, but PTSD along with alcohol misuse worsens PTSD hyperarousal symptoms, anger, and irritability increasing the odds of violent behavior by veterans (Elbogen et.al, 2014). Veterans without PTSD and who never misused alcohol had a rate of subsequent severe violence of 5.3 percent; veterans with PTSD and no alcohol misuse had a rate of 10.0 percent; veterans without PTSD but with alcohol misuse had a rate of 10.6 percent; and veterans with PTSD and alcohol misuse had a rate of subsequent severe violence of 35.9 percent. The cumulative effect of risk factors to include age younger than 34 years old, not meeting basic needs, history of violence before military service, higher combat exposure, PTSD, and abuse of alcohol were more important than individual risk factors in determining risk for violence (Elbogen et.al, 2014). The PTSD symptoms of hyperarousal, anger and irritability with alcohol misuse impact veterans because they increase subsequent violence and make the veterans and communities less safe.

Criteria C and G.

PTSD impacts service members’ and veterans’ mental health and quality of life, and PTSD. Symptom Criterion C and G were addressed by Doctor, Zoellner & Feeny (2011). Participants in the study consisted of 184 individuals, 141 being female, with chronic PTSD at two treatment sites in different U.S. regions. The three commonly used methods to determine quality-of-life estimates are the SG (standard gamble), TTO (the time tradeoff), and the VAS (visual analog scale). To carry evaluation of the quality of life predictors, a linear mixed-effects regression model was performed. Participants completed a current health summary with four domains (Re-experiencing, Avoidance, Arousal, and Anxiety and Depression) with three levels of dysfunction. The results indicated that arousal and anxiety or depression were associated with decreased current health quality-of-life estimates (Doctor et.al, 2011). However, avoidance and re-experiencing of trauma were not associated with lower quality of life. The researchers suspected avoidance was a coping mechanism for some individuals with PTSD. By using avoidance as a coping mechanism, these individuals did not re-experience traumatic events like those who did not cope by avoidance (Doctor et.al., 2011).

Impacts of PTSD

Military members and veterans may suffer from mental disorders resulting from post-traumatic stress such as depression and anxiety and consequently engage in risky behaviors such as alcohol and drug abuse. A study by Cohen, Gima, Bertenthal, Kim, Marmar & Seal (2010) reported the prevalence of mental disorders in veterans coming back home after combat operations in Iraq and Afghanistan as the following:

The most prevalent mental health disorder in this study population was PTSD (21.5%), followed closely by depression (18.3%), adjustment disorder (11.1%), anxiety disorder (10.6%), substance use disorder (8.4%), and alcohol use disorder (7.3%).

In a study conducted on risk-taking behaviors and symptoms of PTSD in Vietnam, Post-Vietnam and OEF/OIF veterans recruited from outpatient clinics in a Midwestern Veterans Affairs Medical Center, risk-taking behaviors were defined as purposeful behaviors that involve potential negative consequence or loss. A 42-item risk-taking self-report survey was developed for the study with four subscales of aggression, risky sexual practices, substance abuse, and thrill seeking. Also, the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption (AUDIT-C) instrument was used to identify individuals with alcohol abuse. Individuals who screened positive for PTSD scored higher on the total risk frequency scale; higher on all four subscales (aggression, risky sexual practices, substance abuse, and thrilling seeking) and the alcohol abuse scale. The OEF/OIF veterans scored higher on the Aggression subscale; higher counts of Aggression; and risky sexual practice items. OEF/OIF veterans scored higher on the Aggression subscale because 72 percent reported “Yelling or making angry hand gestures while driving.” This is believed to be due to the guerilla warfare and improvised explosive devices veterans of OEF/OIF are exposed to in convoys during deployment. The study also found a relationship between PTSD and veterans having unprotected sex, which could contribute to the spread of sexually transmitted diseases. PTSD has been associated with suicide and suicidal ideation in previous research and this study found suicidal ideation was four times (53.9 percent) greater than the general population (13.5 percent) (Strom et al., 2012).

In a qualitative study on stigma associated with PTSD, a convenience sample of 16 OEF/OIF veterans was used, the majority of which were male, diagnosed with PTSD and seeking mental health care at the Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System. Four focus groups were interviewed using an interview guide developed to elicit veterans’ understanding of and response to the public’s attitudes toward PTSD. This study found:

Five major themes emerged from the data. Participants: (a) were aware of many stigmatizing labels, (b) tended to disagree with most of these stereotypes and often resisted them rather than self-stigmatizing, (c) most valued support from their peers, (d) avoided treatment, and (e) perceived that having PTSD differed from having other mental health disorders.

Salient points from the interviews were threefold: military personnel delayed seeking treatment because they did not want to be diagnosed with PTSD; their perception that the civilian population blames military personnel suffering with PTSD because military service is voluntary; and their perception that the civilian population has less sympathy for combat-related PTSD than PTSD from other traumatic events. The veterans believed that only other combat veterans with PTSD could provide understanding and support, suggesting peer-based outreach programs would be beneficial (Mittal et al., 2013). This is problematic with the downsizing of military medicine in the 1990s, and the apparent inability of the Veterans Health Administration to care for the volume of veterans needing care. In 2014, the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act was passed to provide funding for and access to non-VHA center health care for service members and veterans. The act transferred the care of military personnel from a civilian healthcare system that does not have the expertise to care for the unique needs of military personnel and cannot relate to the occupational stressors (Mankowski & Everett, 2016).

Treatment of PTSD

Presently, there are three dominant treatments for PTSD. The first is Prolonged Exposure Therapy (PET), the second is CPT (Cognitive Processing Therapy), and the third is EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing). McLean and Foa (2011) explained that CBT (cognitive-behavioral therapy) is a set of therapy options that includes exposure techniques, cognitive restructuring (CR) and anxiety management. A study conducted by Meyers, Strom, Leskela, Thuras, Kehle-Forbes & Curry (2013) reported the VA and D.o.D recommend Prolonged Exposure (PE) and Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) as first-line treatments for PTSD. The study by Meyers, Strom, Leskela, Thuras, Kehle-Forbes & Curry (2013) used Foa and Rothbaum’s (1998) definition of Prolonged Exposure Therapy from their book Treating the Trauma of Rape: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for PTSD. “PE is a treatment for PTSD that includes psychoeducation, imaginal retelling of the traumatic event, and in vivo exposure exercises” (p. 95). Besides, they also used, the definition provided by Resick and Schnicke (1992) in their article “CPT is a treatment for PTSD which involves writing of the traumatic event and challenging of unhelpful beliefs, or “stuck points,” that resulted from the trauma and are serving to create and promote symptoms” (p. 96).

Prolonged exposure therapy and CPT were created to treat female rape victims who in most cases, have experienced a single trauma. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) was still yet another endorsed and practiced therapy for PTSD. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) focuses on “desensitization” not replacing traumatic images. The traumatic image is not intentionally replaced but changes by free association. Eagle and Kaminer’s (2015) overview of traumatic stress reinforced that the evidence-based treatments for PTSD are Prolonged Exposure Therapy (PE), Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT), and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR).

Knowledge Deficit among Veterans Regarding PTSD

Compton’s (2011) theses on Knowledge and Acknowledgement of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Effects on Military Couples stated there is a lack of a reliable scale for measuring PTSD and a 10-question multiple-choice assessment was developed specifically for the study to measure the service-members’ knowledge of PTSD. One study which focused on knowledge deficit among veterans regarding PTSD included 44 U.S. military veterans from the Vietnam and Afghanistan/Iraq wars, 14 of which were female, and 30 were men receiving mental health treatment. The interventions used were interviews, self-report questionnaires for veterans seeking PTSD disability benefits, a PTSD symptom inventory (PTSD Checklist), the Patient Health Questionnaire—Depression Module, and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test—Consumption Questions. Findings indicated that one of the barriers to treatment initiation was knowledge barriers – “Participants identified lack of knowledge about PTSD, the types of trauma that can cause PTSD (e.g., sexual trauma), and what services were available as barriers to help-seeking. Lack of knowledge occurred at both the societal and individual levels.” (Sayer et al., 2009, p. 246).

Another study used cognitive-behavioral telephone interventions to ask 143 military men and women who served in Operation Enduring Freedom or Operation Iraqi Freedom and who screened positive for PTSD by the PTSD Checklist-Military Version (Weathers et.al., 1993) about their reasons for not seeking treatment. The results found barriers to seeking treatment by veterans who have PTSD were, 40 percent had concerns about treatment, 35 percent were not emotionally ready for treatment, 16 percent were concerned about the stigma and negative consequences to seeking treatment, and finally eight percent cited logistics problems and were not able to get to treatment. With 40 percent concerned about treatment, education programs are so important (Stecker et.al. 2013).

An online survey conducted to assess knowledge of PTSD found that people with PTSD symptoms lack knowledge about PTSD and effective treatments for the disorder. The study was in agreement with Compton’s (2011) thesis that a valid measure to assess PTSD knowledge does not exist and locally constructed tests are developed to detect changes in PTSD knowledge in pre-to post-intervention studies. In this study of 301 adults, 50 percent of which were veterans, and screened positive for PTSD, three domains of PTSD knowledge were measured: trauma recognition, symptom recognition, and treatment recognition. Findings indicated participants were least knowledgeable about PTSD treatment options (Harik et.al. 2016).

Two studies involving patient decision aids (PtDAs) were conducted to allow for input from patients regarding patient’s knowledge of PTSD. The first was a randomized controlled clinical trial of a patient decision aid to improve patients’ knowledge of PTSD versus a control group with 132 males and ten female veterans. Participants’ knowledge of PTSD was measured by a 24-item true-or-false questionnaire developed by the investigators. The results of the study revealed that participants who reviewed the patient decision aid scored higher on the PTSD knowledge questionnaire and had less conflict choosing a treatment (Watts et al., 2015). In the second study, Understanding and meeting information needs for patients with posttraumatic stress disorder, 16 men and three women participated in an informational needs assessment of veterans with PTSD to obtain the information necessary to develop a patient decision aid (PtDA). The patients indicated, on the needs assessment, the desire to learn about PTSD symptoms and treatments. A patient decision aid on the “Treatment Options for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder” was developed for patients to use either alone or with staff assistance. Patient decision aids allowed the patient to acquire more knowledge about PTSD, make informed decisions regarding evidence-based treatments, and ultimately improved PTSD symptoms (Watts et.al. 2016).

Partners of military members can play a critical role in helping veterans recognize and seek mental health care for PTSD, but they too have a knowledge deficit regarding PTSD, its symptoms, and treatments. A study of 497 respondents, the majority of which were spouses of army members, used a web-based post-traumatic stress disorder education program to improve knowledge of PTSD and a 25-item pretest/post-test to assess knowledge. The results of the study indicated that correct responses on the PTSD knowledge test increased from 13.9 to 18.7% after participating in the web site education program. After 10 days, participants returned to the site resulting in 57 percent of the spouses talking to the service member about their symptoms, and 34 percent of the spouses encouraging the service member to obtain medical care for their PTSD (Roy et al., 2012). A previous study by Buchanan, Kemppainen, Smith, MacKain, and Cox (2011) supported this study. A study conducted Buchanan, Kemppainen, Smith, MacKain, & Cox (2011 state:

A noteworthy finding is that spouse/intimate partners of combat veterans had very little knowledge about the symptoms of PTSD. Only one-third of the participants in this study reported receiving formal training on PTSD. The majority of participants in this study obtained facts about PTSD through informal sources, including the media (e.g., news, movies, Internet), family and friends diagnosed with PTSD, or from spouses of other active duty military.

A survey by Roy, Taylor, Runge, Grigsby, Woolley & Torgeson, (2012) developed the 25-item PTSD Knowledge Questionnaire for the Web-Based Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Education for Military Family Members study and stated “Note that in order to assess reliability you would essentially have to have some gold standard to compare it to—in other words, some measure of how knowledgeable people are with regard to PTSD, which does not exist, to the best of my knowledge.” M. Roy (personal communication, March 6, 2017). The evidence indicated there is no empirical research that examines the lack of knowledge of PTSD specifically in female veterans. However, it is well accepted among experts as reflected in studies on barriers to care for female veterans, studies that include both male and female veterans, and studies involving partners of veterans.

Finally, Ryan’s (2016) dissertation on Civilian Perceptions of Combat PTSD As It Relates to Stigma and Social Support stated there is not a reliable measure available to measure public knowledge of PTSD and used a 12-question, multiple-choice PTSD Quiz developed by Stoppler (2011). Stoppler is a U.S. board-certified anatomic pathologist and a member of the medical editorial board of MedicineNet.com, and developed the test to be published online by Medicine Net.

Females with PTSD

Historically, the U. S. military was established as a male-oriented career field wherein women served in ancillary roles such as nurses. Over the years the role of women in the military has expanded and this has contributed to an increase in female military personnel experiencing PTSD. According to the Women Veterans Report (Department of Veterans Affairs, 2017), in 2013 the Secretary of Defense rescinded the 1994 Direct Ground Combat Definition and Assignment Rule for Women which removed barriers for women to serve in combat career fields. The change in policy increased the opportunities for women and contributed to a combined strength of 200,000 women serving on active duty in 2015. Since the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, more than 700,000 women have served in the military. According to the Department of Veterans Affairs (2016), as at September 30, 2016, the total number of U.S. female veterans was 2,051,484, while in New Jersey the female population was 33,197. One of the consequences of more women serving particularly in direct combat roles is an increased suffering arising from the physical and psychological wounds of combat. Sadly, many of these U.S. female veterans have been wounded and 161 females have died from combat and non-combat related incidents (Women Veterans Report, Department of Veterans Affairs, 2017).

The significance of U.S. female service members and veterans being diagnosed with PTSD and going untreated was the effects it has on their health; their interpersonal relationships with partners, children, family, employers; economics, homelessness, and their reintegration in the community (Mankowski & Everett, 2016). Not all VHAs have women’s clinics to address the specific needs of female veterans. Homelessness among female veterans that are single mothers with PTSD, depression, and substance abuse disorders was increasing (Mankowski & Everett, 2016). A study conducted by Mankowski & Everett (2016) posit that it is the responsibility of clinic health care providers to assist female veterans to heal, adjust, and reintegrate into society.

In an observational study in which 1,202 veterans completed a web-based survey to determine the health care needs of female VA service users, it was determined that 23.4 percent of female veterans use the VA as their main source of health care (Tsai et.al, 2015). Compared to women who did not use the VA for health care, women who did use the VA are more likely to be minority, low income, unemployed, combat veterans, have a disability, screen positive for PTSD, and report poor mental-health functioning based on the Short Form-8 (SF-8). Therefore, based on the findings of this study, it is critical that gender-specific health care services and outreach initiatives are developed for this patient population (Tsai et al., 2015).

In a cross-sectional survey of 484 female veterans from four different VHA sites, the most important mental health services were prioritized as PTSD, depression, coping with chronic medical conditions, pain management, sleep disturbance, and weight management (Kimmerling et al., 2015). The study found that participants wanted primary care and mental health care services located together, not separate specialized mental health clinics. Also, the women were willing to receive tele psychiatry as a means of receiving care for mental health issues, which would provide accessibility and convenience to mental health specialty care (Kimmerling et al., 2015). In another cross-sectional survey of 3,607 women veterans, computer-assisted telephone interviews were used over nine months to identify healthcare delivery preferences and develop healthcare programs based on their military service era. Women veterans of OEF/OIF/OND rated primary care, mental health care, and OB/GYN services as most important and expressed the need for these services to be co-located (Washington et.al, 2013).

One study found specifically that women deployed to OIF/OEF more often developed major depression and substance abuse disorder than deployed men (Shen et.al, 2012). Shane and Kime (2016) reported 20 veterans commit suicide every day, which is a drop from 24 veterans who committed suicide a day in 2009. They also reported the suicide rates in female veterans rose by more than 85 percent from 2001 to 2014, compared to civilian women whose suicide rate rose by about 40 percent. Carroll Chapman & Wu (2014) found nine studies examining completed suicides among veterans and concluded PTSD increased suicide risk in female veterans when it occurred in the presence of another mental disorder and substance abuse.

Common PTSD comorbidities are depressive disorders, substance use disorders, anxiety disorders, alcohol abuse, panic attacks, and suicidal ideation (Galatzer-Levy et.al. 2013). Four hundred and nine individuals participated in the study, of which 304 were female, from the National Comorbidity Study-Replication (NCS-R) and had a lifetime diagnosis of PTSD. The investigators used Latent Class Analysis (LCA) (latent = not directly observable) to determine common patterns of lifetime comorbidity in individuals diagnosed with PTSD. Participants were diagnosed with PTSD using the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI). The comorbid disorders under study that occurred following the reported traumatic event that were analyzed as follows: anxiety disorder (AD), drug dependence (DD), dysthymia, major depressive episode (MDE), generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, and specific phobia (SP). Participants were interviewed about the frequency and severity of PTSD symptoms and responses recorded on a Likert-type scale. The history of suicidal ideation and exposure to six types of traumatic events were also recorded.

The results of this study were that individuals with lifetime PTSD develop three patterns of comorbidities. In the first class, or low comorbidity, individuals have a modest probability of having a lifetime diagnosis of major depressive episode (MDE) and lifetime suicidality. In the second class, individuals have a higher probability of life-time suicidal ideation and a moderate-to-high probability of mood and anxiety disorders. Major depressive episode (MDE) had a high probability of occurring after the PTSD diagnosis. In the third class, individuals have a high probability of lifetime suicidal ideation, moderate-to-high probability of anxiety and mood disorders, and moderate-to-high probability of substance dependence disorders. Moreover, MDE had a high probability of occurring after the PTSD diagnosis. The researchers also surmised that with greater PTSD symptoms there was greater comorbidity (Galatzer-Levy et al., 2013).

Differences between Female and Male Service members and Veterans

In a study conducted on 7,251 active duty soldiers from a large Army installation who had been deployed in support of OIF/OIF, the female participants differed demographically from the men; there were more African-Americans, they had higher levels of education, and there were more officers (Maguen et.al, 2012). The women were more likely to be single, widowed, divorced, or separated, and more likely not to have children. There were several measures used: a questionnaire to assess combat exposure and military sexual assault, the Primary Care PTSD Screen (PC-PTSD; Prins et al., 2003), the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Kroenke and Spitzer, 2002) and the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders et al., 1993). Using regression analyses the researchers found that men reported alcohol abuse more than women, women reported depression symptoms more than men, but there were no gender differences with PTSD symptoms. The researchers found a stronger association between injury and PTSD symptoms for women than men.

In still yet another study, using a cross-sectional mail survey of 2,341 U. S. military veterans who had deployed for OEF/OIF, PTSD was found to be no greater in female combat OEF/OIF veterans than male veterans (King et.al, 2013). The 17-item PCL-Military version (Weathers et al., 1991) was used by the participants to self-report measures of PTSD symptoms and item response theory (IRT) was used by the researchers to reveal if symptom reporting varied by gender. As in other studies, this showed that following trauma exposure military men and women had similar profiles of post-traumatic stress symptoms.

In a national mail survey of OEF/OIF veterans of 2,344 carried out in all branches of the military supported that women veterans and male veterans were equally likely to report symptoms of PTSD. Numerous scales were used in this study – the Deployment Risk and Resiliency Inventory (DRRI), Sexual Harassment Scale, General Harassment Scale, Unit Support Scale, Combat Experiences Scale, Aftermath of Battle Scale, Prior Stressors, the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-Military (PCL-M), the Depression Scale (CES-D), the Anxiety Subscale of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) and the CAGE Questionnaire. The evidence showed that there are no gender differences in PTSD among OEF/OIF veterans. Women veterans were more likely to report depression symptoms and male veterans were more likely to report alcohol abuse. However, this study found that women veterans were more likely to report deployment stressors. Deployment stressors included sexual harassment, general harassment, lack of social support, and post-deployment adjustment problems, whereas, male veterans reported more combat experience (Street et al., 2013).

A study of 159,705 veterans of OEF/OIF seeking healthcare through the VA for PTSD used VA administrative data and found that female veterans with PTSD were more likely to be African-American and single. The females with PTSD were more likely to use outpatient primary care and mental health clinics, as well as emergency rooms, than males with PTSD. However, men with PTSD were more likely to have higher inpatient mental health hospitalization than women. Comorbid conditions, like depression and alcohol abuse, with PTSD increased the use of all healthcare type services for both women and men (Maguen et al., 2012).

Barriers to Care

There are many barriers to female service members and veterans receiving mental healthcare for PTSD. In the Study of Barriers for Women Veterans to VA Health Care (Department of Veterans Affairs, 2015) 64,509 women who received care in 21 Veteran Integrated Service Networks (VISNs), completed a Barriers to Care survey. The Barriers to Care survey was a 45-minute Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing (CATI) survey that utilized professionally trained female interviewers and reported a response rate of 13.2 percent. In this study, nine barriers to care were identified. Barrier two was identified as outreach specifically addressing women’s health services, with only 67 percent of the user population reporting having received information on Women’s Health Services. Barrier eight was identified as mental health stigma. Twenty-four percent of women reported they were hesitant to seek care for mental health issues. Of those who reported hesitancy, 62 percent cited fear over the medicines used and 36 percent reported they were not sure seeking care would help.

A study that examined the feasibility and desirability of web-based mental health screening and individualized education for female OEF/OIF Reserve and National Guard war veterans included 131 OEF/OIF Reserve and National Guard (RNG) Army and AF servicewomen deployed in the past 24 months. Forty-one percent screened positive for PTSD. The study was conducted in two phases. In phase one participants completed a web-based online post-deployment screening, an individualized web-based psychoeducation, and a satisfaction survey. In phase two, telephone interviews were conducted to assess perceptions of the screening, the web-based psychoeducation, and care access. In phase one of the study, using web-based psychoeducation, 31 percent of the females decreased their discomfort with seeking care for post-deployment symptoms; 48 percent received new information; 39 percent said they would seek care with the VA; and 27 percent said they would seek care from non-VA healthcare. In the phase two telephone interviews, the reasons the female veterans gave for not using the VA post-deployment for mental health care were “stigma” and lack of knowledge about treatment options for women (Sadler et al., 2013).

A study on perceived barriers to care among veterans’ health administration patients with post-traumatic stress disorder included a total of 490 male and female VA outpatients diagnosed with PTSD within the last six months. The sample consisted of 137 male OEF/OIF patients (19 percent response rate), 111 female OEF/OIF patients (33 percent), 122 male pre-OEF/OIF patients (51 percent), and 120 female pre-OEF/OIF patients (41 percent). Three tools were used for this study. The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D, Radloff, 1977) was used to measure clinical depression. To assess how severe the post-traumatic stress disorder and its symptoms were the Impact of Events Scale-Revised (IES-R; Weiss & Marmar, 1996) was used. Twenty-five items from the Barriers to Help Seeking Scale (Mansfield et.al, 2005) and items from a literature search on why men and women do not seek help (Vogt, 2011) were used to develop the tool to assess barriers to access in VA care. The results of this study showed individuals with more PTSD symptoms perceived more barriers to care. The study also found younger veterans and Caucasian women did not feel they fit into VA health care since many perceive it as a male oriented system. Younger veterans and female veterans need to be educated on current services offered through the VA (Ouimette et al., 2011). A qualitative inquiry that explored health-related quality of life of female veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder reinforced this perception that the VA healthcare system is male oriented and lacks female-centric care and support networks (Haun et al., 2016).

Synthesis of the Evidence

PTSD impacted military service members and veterans and all aspects of the quality of their lives, to include health, relationships, and work. There are many types of PTSD treatments, but currently the three evidence-based treatments approved by the VA are Prolonged Exposure Therapy (PET), Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR). Despite the prevalence of PTSD among military personnel, service members still lack knowledge of PTSD and fail to recognize the symptoms of PTSD. PTSD impacted all service members, and female service members had particular needs that must be addressed. If barriers to care for female service members are left unaddressed and solutions not implemented, outcomes to care for women veterans will undoubtedly be poor.

Chapter 3: Knowledge Acquisition Theoretical Framework and Blueprint

Theoretical Framework

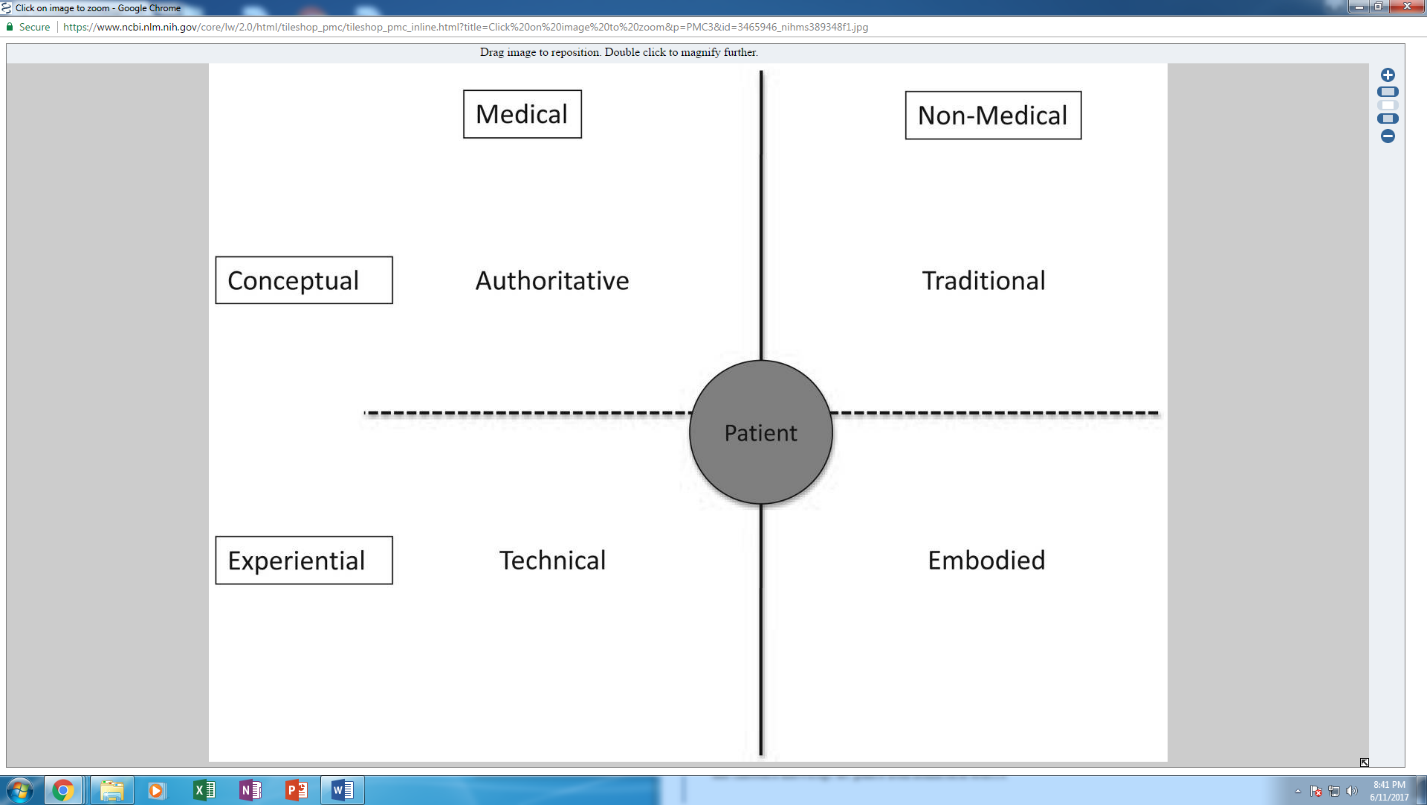

The theoretical framework used for this study was the model of knowledge acquisition developed by Mendlinger and Cwikel (2005/2006) and applied to early stage breast cancer (Warren et.al. 2012). The model presented four types of knowledge: authoritative, technical, embodied, and traditional. The theory was designed to explain how people obtain new knowledge. The researchers developed the theory to explain that traditionally young Israeli women obtained knowledge regarding puberty, menstruation, sex, reproduction, and child care through older females. However, the immigration of women from other cultures has changed how young women obtain knowledge from traditional to authoritative. Both authoritative and the technical knowledge is conducted by healthcare providers. Authoritative knowledge includes knowledge on understanding PTSD, the symptoms of PTSD, and the types of treatments available for PTSD. Authoritative knowledge on PTSD extends to psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric nurse practitioners, social workers, and counselors that have received specialized training in the care of persons with PTSD. Technical knowledge referred to feasible options and limitations with the healthcare system. The media frequently reports that the VA does not have enough trained mental health providers to treat the number of veterans with PTSD. Different evidenced based practices such as group treatments or accelerated treatments are under study to determine their effectiveness in meeting larger numbers of veterans affected by PTSD and help this patient population at a faster pace. The benefits of technology, like patient decision aids (PtDA) and tele psychiatry, are under exploration to meet the increasing needs of patients with PTSD.

Knowledge gained outside the medical system includes traditional knowledge and embodied knowledge. Traditional knowledge is information that was passed down from generation to generation by rituals and history. Traditional knowledge in the veteran population was lacking because veterans from previous conflicts have avoided thinking and talking about the traumatic events and feel it is unacceptable to talk about the trauma. Embodied knowledge was knowledge gained from personal experience and from relatives and friends. This goes to the importance of female veterans with PTSD connecting with and having the understanding and support from female veterans; and learning from them regarding how to treat and live with PTSD. Different types of knowledge can be obtained from one source. The Internet is a source for a lot of information, but not all the information found on the Internet is correct and evidence-based. Also, due to a healthcare provider’s training, the information provided to a patient may be biased.

Justification and Relevance of the Framework.

The type of knowledge provided in this study was authoritative because it was expert medical knowledge that is evidence-based intended to inform female service members and veterans about PTSD. The information was being presented by a Doctorate in Nursing Practice candidate and the nursing role is authoritative. Traditional knowledge based on stories handed down from one generation of veterans to the next was lacking because of the PTSD symptom of avoidance and veterans not wanting to relive traumatic experiences. Besides, service members and veterans do not feel comfortable sharing these experiences with others and fear being viewed negatively by people. The project positively influenced some aspects of traditional knowledge because of its design using small groups. Participants shared experiences with each other and compared to the authoritative knowledge for completeness, corrections, and validation. The author of the project had embodied knowledge, or knowledge gained from personal experience and from relatives and friends. The author was born at Fort Riley, KS, and was the daughter of a career USA field artillery officer who served two tours of Vietnam. Growing up as an “army brat” one was surrounded by service members and their families dealing alone with PTSD.

As a college graduate, the author joined the USAF and served as a nurse for 21 years. While flying aeromedical evacuation at Ft. Bragg, NC, married a USAF aviator, and became the sister-in-law of a USA paratrooper. An individual can be well educated and highly intelligent on the academics of PTSD but may not have experience and be able to recognize the symptoms in themselves or others. Also, the symptoms of PTSD are broad and may be delayed in onset, so the diagnosis can be difficult to make. The best way to acquire accurate information regarding PTSD was through authoritative knowledge.

Figure 2. Model of Knowledge Acquisition in Early Stage Breast Cancer, Warren et al. (2012)

.

Blueprint

The blueprint used in this study was the Logic Model from the University of Wisconsin -Extension (2002). The blueprint allowed for inputs, outputs, and short, medium, and long-term outcomes and provided a roadmap for the project. Refer to Figure 3: Program Development and Evaluation DNP Project: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in U.S. Female Service Members and Veterans Logic Model.

Figure 3. Logic Model: University of Wisconsin-Extension

Program: Program Development and Evaluation DNP Project: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in US Female Service Members and Veterans Logic Model

Situation: While conducting research on PTSD, this author discovered US Service Members and Veterans reported having a knowledge gap regarding PTSD, and it has been widely publicized in the media that there is a lack of access to healthcare for US Service Members and Veterans.

| Inputs | Outputs |

Outcomes — Impact |

||||||

| Activities | Participation |

Short |

Medium Long |

|||||

| What we invest

Completed Literature Review/ Research on PTSD Instrument: Knowledge of PTSD Questionnaire (KPTSD), Eval, &Survey of intent/Global Questionnaire Partners – Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital Staff / Volunteers Project site-New Hanover Townships’s Senior Citizen Center Educational Program on PTSD Equipment-projector & audio equipment for educational presentation Time/ Money Capstone Committee |

What we do

Conduct education program on Knowledge of PTSD Survey of Intent – with increased knowledge will they seek health care

|

Who we reach

US Female Service Members & Veterans Our Lady of Lourdes Decision-makers

|

What the short-term results are

Increased knowledge of PTSD Awareness of signs and symptoms of PTSD Increased knowledge of treatments for PTSD (non-pharmacological and pharmacological) Positive attitudes & knowledge for obtaining local health services & early intervention |

What the medium-term results are

Action – to treat US Female Service Members & Veterans w/PTSD

|

What the ultimate impact(s) is

Conditions – Civic/ social/moral obligation Economic-cost to duplicate forms; food, Local health fairs 2nd study with Auburn U for The Combat PTS(D) Reintegration Workbook Program Address Military Sexual Assault & care of victims

|

|||

| Assumptions | External Factors | |

| Participants will be provided a Screening & Crisis Intervention Program phone number. In an emergency, an ambulance will be called & the individual will be transported to the nearest ER.

Increased knowledge regarding PTSD will result in early intervention & care. Access to healthcare facilities will result in increased care of US female veterans.

|

The Veterans Choice Program does not allow veterans to seek civilian care if the VA is able to see them in 30 days. |

Chapter 4: Design and Methodology

Project Design

The project was a DNP program development and evaluation project as described by Moran, Burson, and Conrad (2017) that included an intervention to increase the knowledge of PTSD and recognition of its symptoms and treatments in U.S. female service members and veterans. The aim of this project was to answer two questions:

1. Do female U.S. service members and veterans who participate in the Knowledge of PTSD Education Program score higher on the PTSD Knowledge Questionnaire after participating in the program? And

2. Does knowledge of PTSD obtained through the education program for female U.S. service members and veterans encourage female veterans to seek medical care? The project used a pretest/post-test design to assess knowledge acquisition. After participants signed a consent form and completed a demographics form, they took a PTSD Knowledge Questionnaire. The PTSD Knowledge Questionnaire assessed individuals’ knowledge of the definition of PTSD, along with common signs and symptoms of PTSD. It also assessed risk factors for developing PTSD; PTSD comorbidities; and knowledge of VA and DoD approved first-line treatments to obtain a baseline prior to the participants viewing an introductory slide on PTSD and five, three-minute videos. The Knowledge of PTSD Questionnaire was repeated after the participants viewed the slide and videos, and increased scores on the PTSD Knowledge Questionnaire was indicative of increased knowledge of PTSD. The participants had the opportunity to evaluate the videos by completing an evaluation form. Participants recognized PTSD in oneself and understanding what one is experiencing can be the motivation to eliminate negative behaviors and improve positive behaviors. To determine if participants felt the need for additional medical assistance with PTSD, a survey of intent was completed by the participants.

Ethical aspects in implementing the project according to Peirce and Smith (2013) were autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, veracity, and fidelity. Patients were informed participants in the decision-making process. Written informed consent (Appendix D) was obtained when the individual presented for the education program and is being maintained at Rutgers University in a secure, locked cabinet for six years and will then be destroyed. To ensure participant anonymity, all packets were assigned a random number. Only the consent form contained both the participants name and number. The consent form was separated at the completion of the session and stored as previously noted.

The ethical principle of non-maleficence or not doing harm was addressed by having the local Screening and Crisis Intervention Program address (218 Sunset Road, Willingboro, NJ and phone number (609-835-6180) available for participants on a non-emergency basis. If an emergency occurred an ambulance would have been called and the individual transported to the nearest emergency room. No emergency situations occurred.

Setting

The educational program was conducted at a senior citizen center/conference room (Appendix A).

Population/Sampling

The population was a purposive sample consisting of both female service members who are currently in the military, as well as veterans, from a military base in New Jersey and the surroundings of the New Jersey region. Through a power analysis, the total number of participants who needed to be included in the project was 26 (Appendix B).

Inclusion criteria was:

- The ability to read, write, speak, and understand English.

- Female service members (US Air Force, Army, Navy, and Marine) who are currently in the military (active duty, reserve, or Guard), as well as veterans.

- Between the ages of 18 and 64.

- Those who have or have not been diagnosed with PTSD AND have not been treated with Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (PE, CPT, or EMDR) for PTSD.

- Being legally and cognitively capable of signing their own consent form.

Exclusion criteria for subjects for the study was:

- Treatment for PTSD with Cognitive Behavioral Therapies.

Recruitment Strategies

The participants were recruited by paper advertising through active duty, reserve, and Guard units at a military base in New Jersey (Appendix C). The participants were able to register for the program via a designated phone number.

Demographics

A demographics form was completed by all participants and the following demographics was requested: military grade, branch of military service (USA, USAF, USN, USMC), duty status (active duty, reservist, Guardsman, veteran), career field/specialty (MOS, AFSC), age, race, years of military service, time period served (1970-present, 1980-present, 1990-present, 2000-present, 2010-present), number of combat theater deployments since 2001, length of longest deployment, disability (“Yes”, “No”), relationship status (married, divorced, single), number of children, highest formal education completed, and spirituality (Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu, Nondenominational, Other, None) (See Appendix E).

Outcome Measures

A pretest-post-test design was used to measure the effectiveness of the intervention. A 25-item questionnaire developed by Roy et al. (2012) was used as the pretest and post-test (Appendix F). Permission to use the questionnaire in this study was received from Dr. Roy by email (Appendix G). An email from M. Roy (personal communication, March 6, 2017) confirmed the questionnaire has not been validated in another population.

The questionnaire has face and content validity based on Roy et al.’s (2012) study with a level of statistical significance of 0.05, an effect size of 1.2, and the standard power of 80 percent or 0.8. Since reliability of the questionnaire has not been determined, and there is not another tool available at this time, Roy’s Knowledge of PTSD Questionnaire was the best option from the literature. A limitation of the test was that it was developed for family members and not for veterans.

Following the pre-test, the intervention was started. The intervention consisted of an introductory slide provided by this author (Appendix H) and showing five, three-minute a piece, videos provided by the National PTSD website. The introductory slide is designed to cover information gaps in the videos regarding general knowledge of PTSD. The videos were available on the National Center for PTSD website, in the public section, under animated whiteboard videos (Appendix I). The title of the videos are as follows:

- What is PTSD?

- Treatment: Know Your Options

- “Evidence-based” Treatment

- Cognitive Processing Therapy

- Prolonged Exposure

Video 1: What is PTSD? Reviewed events that can cause PTSD like natural disasters, accidents, & war. Defined PTSD as a stress related reaction after a trauma. Provided 4 types of symptoms people with PTSD have & they are re-experiencing, hyperarousal, feeling worse about yourself or the world, & avoidance. Video 2: “Evidence-based” Treatment: What Does It Mean? Defined “evidence-based” treatments as treatments that provide the best chance for recovery because multiple, high quality scientific studies have been done on these treatments & experts agree these treatments work. Video 3: PTSD Treatment: Know Your Options: Two main types of treatments were discussed. One was therapy and the other was medications. Types of therapy are Cognitive Processing Therapy, Prolonged Exposure Therapy, and Eye Movement Desensitization Reprocessing. The types of medications used are the SSRIs or SNRIs antidepressants. Comorbidities with PTSD were identified as chronic pain, depression, substance abuse, history of traumatic brain injury, and insomnia.

Video 4: Cognitive Processing Therapy for PTSD: breaks the negative thoughts about the trauma by talking to a therapist to change thoughts or writing about the trauma. Video 5: Prolonged Exposure for PTSD: explained how individuals with PTSD avoid situations that remind them of the trauma. Prolonged exposure exposes the individual to events they have been avoiding. The videos were shown using a projector with audio. Permission to use the videos was received from Heather Balch, Health Science Specialist, at the VA National Center for PTSD (Appendix J). Immediately following the videos participants were able to ask questions regarding the material. Participants were then asked to complete the Knowledge of PTSD Questionnaire post-test followed by a Satisfaction with the PTSD Videos Evaluation Form provided by Pratt et al. (2005) (Appendix K). Permission to use the Evaluation Form was provided by Dr. Sarah I. Pratt (Appendix L). Following the Evaluation Form, a Survey of Intent was completed to determine if the participants are motivated to seek medical care (See Appendix M). Each question had two parts. Answers were “Yes” or “No” answers and there was a section for the participants to write comments.

Implementation/Inquiry Plans

Authorization from Rutgers’ institutional review board (IRB) was obtained prior to initiating the project. The project was clearly advertised as an education program only, no patient screening or direct patient care was conducted. No identifiers, other than the participant signing their name on the consent form, was maintained by the DNP student for security reasons (Appendix D). A stipend for participation was not given. Food was provided during the presentation and inspirational adult coloring books and journals were provided if wanted by participants.

Figure 4. Flow Chart

Data Analysis

Demographics

All data was entered into Excel and SPSS by the investigator. The results of the demographics’ forms were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Table 2: Demographics

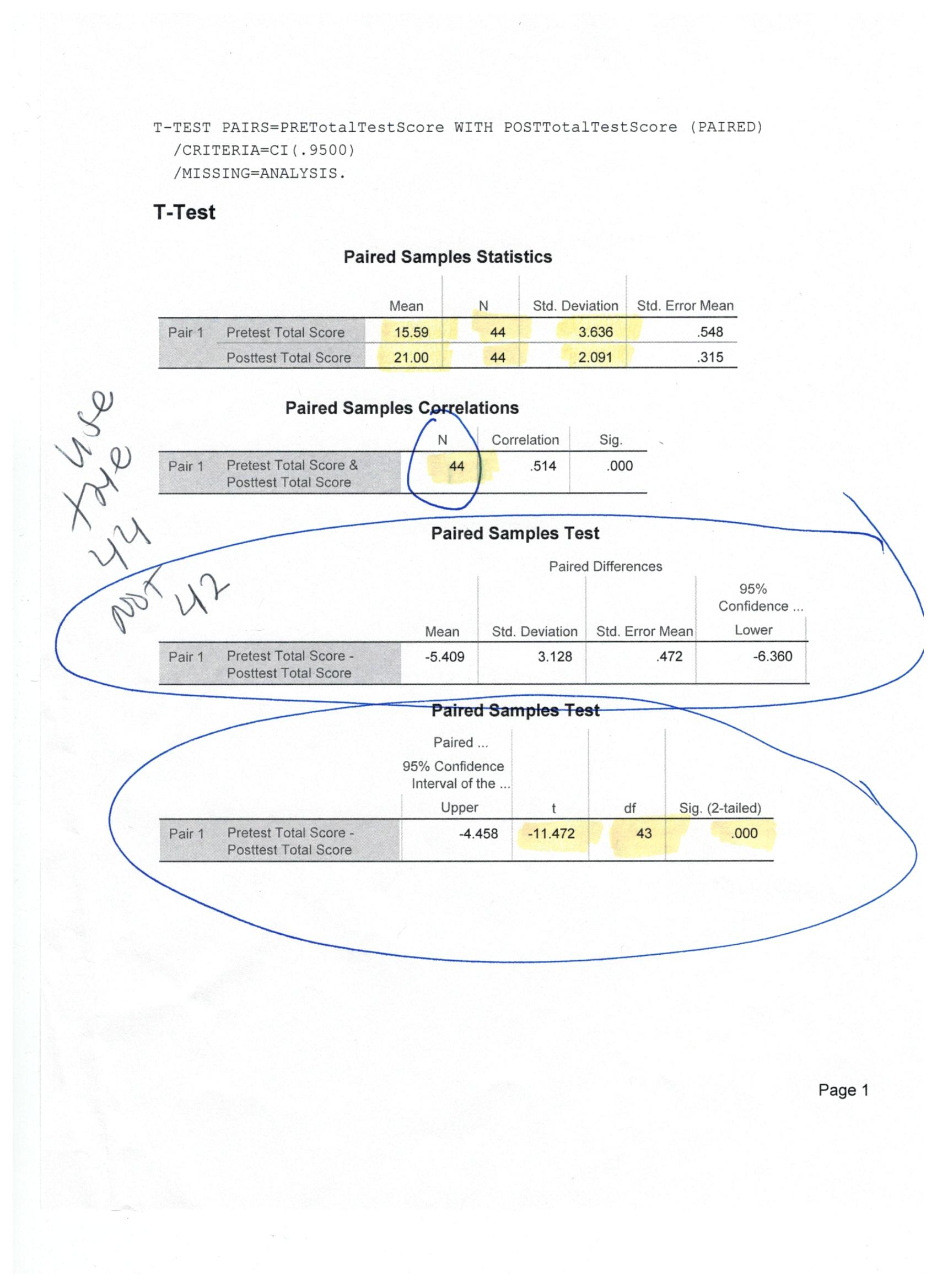

Dependent t-test

A dependent t-test design was used to test the difference between two means of the same group tested twice (e.g., pre-test-post-test). The level of statistical significance was set to 0.05, the effect size was 1.2, and the standard power was 80 percent or 0.8. Using SPSS Version 24, the dependent t-test was calculated. The mean of the post-test 21.0, was significantly higher than the pre-test, 15.59, t(43) = -11.472, p = .000.

Table 3: Dependent t-test

|

Descriptive statistics were used again for both the satisfaction with the PTSD videos evaluation form and the survey of intent. The descriptive statistics conducted for the survey of intent indicated that 18 of the 44 participants would seek medical care and 19 would seek mental health care.

Table 4: Satisfaction with Videos

Table 5: Seeking Care

Limitations of the Study

A limitation of this project, as stated previously, was that the project was submitted to the IRB in August but was not approved until November. Unfortunately, this made it difficult to get subjects for the research due to the holidays and inclement weather and the project had to be extended until February 1, 2018. Also, in retrospect, the primary investigator should have requested from the IRB that the class be allowed to be conducted at Rutgers University – Camden, as well, for the convenience of the female veteran students. None of the female veterans that attend Rutgers University – Camden attended the program. Additionally, the primary investigator regrets not offering the program to both female and male service members. Separate classes could have been offered at two different times, for example, morning classes for females and evening classes for males, and this would have increased the patient population from which to draw from.

Discussion

After completing this educational program on PTSD, participants were able to define and recognize symptoms of PTSD; discuss current types of evidence-based treatments for PTSD; and indicate willingness to seek medical and mental health care. There was statistically significant improvement in the knowledge level of the participants following the education program. An educational program successfully increases PTSD knowledge among female service members and veterans. It is hoped that the results of this study will make U.S. women veterans more knowledgeable of PTSD, its signs and symptoms, and will prompt them to seek care for PTSD when needed. The education program is a sustainable way for female military personnel and veterans to become knowledge regarding PTSD.

Implications for Research

What remains unanswered is how do we better educate service components and its members as well as civilian organizations about PTSD prior to it becoming a problem? Potential areas for future research are to expand this program to male service members and veterans, and family members. Continue educating military personnel and veterans through action research such as health fairs that address the symptoms and treatments of PTSD and connecting veterans to local health care specialists for care. Research on new and better treatments for PTSD, such as accelerated resolution therapy (ART), and stellate ganglion block (SGB) are being studied by the VA for safety and effectiveness and may be accepted as evidence-based practice. Accelerated resolutions therapy (ART) was developed by Laney Rosenzweig, a therapist. The treatment is similar to EMDR with a clinician directing the participant through eye movements, but the traumatic image is replaced by a positive image. Accelerated resolution Therapy (ART) treatments take less time than PE, CPT, and EMDR that take 12 sessions versus ART that takes five sessions (Kip, et al., 2013).

Accelerated resolution therapy is now being studied at the University of Cincinnati Gardner Neuroscience Institute and Cincinnati VA Medical Center due to a grant from the Chris T. Sullivan Foundation. Chris T. Sullivan is the co-founder of Outback Steakhouse (Whitehurst, 2017). Stellate ganglion block (SGB) is a procedure in which a group of nerves in the neck are anesthetized to prevent the flow of epinephrine and norepinephrine from the brain to the rest of the body for the “fight” or “flight” response and relieves the hyperarousal and avoidance symptoms seen with PTSD (Lynch et al., 2016). New approaches using technology, like patient decision aids, smart phone apps for therapy, and telemedicine and telepsychiatry should be explored and implemented if determined to be helpful.

Conclusions

Preventive PTSD education will enable female military personnel and veterans to know the signs and symptoms of PTSD prior to experiencing them and be knowledgeable of the treatments in order to seek care if and when they need it. Knowing the signs and symptoms of PTSD may enable one to identify PTSD in a fellow veteran and encourage them to get the help they need. Finding affordable, local mental health care is not easy and waiting until one is experiencing symptoms is not wise or prudent.