Abstract

The topic of the research is Hospital Readmissions and CMS Penalties. The area has been well explored in the current literature. However, this study aims to conclude in a different direction. It is imperative to understand the ways to alleviate readmissions in U.S hospitals. The secondary data collection was collected from the familiar literature available on the subject. The inductive approach was adopted to undertake this study. The variables used are the affections and operations of patients, age, and sex, the admission (emergency or not), as well as the presence of a hospital stay during the six months previous. Although, the primary and secondary sources are somewhat the same. The total number of articles extracted from the literature is 30. The detailed analyses of the literature included fact sheets, charts, and graphs of trends in readmission in U.S hospitals.

The results reveal that readmissions in the U.S have varied over the period of a decade. There are different ways to alter the readmissions in U.S hospitals. There had been a constant increase in the number of readmissions with the passage of time. The danger of being readmitted, so it is potentially preventable calculated from a Poisson regression model to consider the time of exposure to the risk of readmission. The findings show that most numbers of patients were alive and the risk of readmission is significantly higher among them.

There are a set of recommendations that can improve the rate of readmissions. The U.S hospitals need to be very focused on the issue at hand. Whereas the examination of medical records is relatively expensive, it is recommended to aim the analysis of the services where the readmissions are too numerous. If interest rates are high in all services, it may want to examine a random sample of wrappers of the identified readmissions.

Introduction

Background of the Study

There are several reasons for the rate of detection readmission as a quality indicator of the hospitals. First, it is well documented that an early discharge or sketchy treatment during hospitalization can lead to readmission. Second, readmissions events frequent and, on the contrary deaths may occur as a result of a wide range of diseases. Third, the necessary data to calculate readmission rates and to adjust them according to cases are routinely available in all United States hospitals. Not all readmissions are problematic. Some are planned at the time of discharge of the patient, for example, a cholecystectomy after a hospital stay for cholecystitis. Some authors they proposed to consider only the emergency re-admissions that had become required within a month after discharge. This procedure, conversely, is problematic. Numerous readmissions emergency, in fact, are due to a new illness without ties to the previous hospitalization. A patient may, for example, be hospitalized following a car accident three weeks after it is finished at the hospital for a heart attack (Tsai, Joynt, Gawande, & Jha, 2013).

Some readmissions Planned are also justified by the care of a complication or from reoperation at the same surgical site. Finally, it should readmissions distinguish between planned and provided. A birth that follows a shelter for a difficult pregnancy always takes place in an emergency (unplanned), although it is apparently expected. Their situation is similar to the case of transplants given that the patient undergoes in-depth visits to ensure he is a candidate, but generally, you do not know the date of the readmission receiving the organ. It is therefore not possible to define the character expected of readmission based on the procedures set for Admission (planned or emergency). For these reasons, it is necessary to distinguish some situations’ clinical comparison of the medical data of the first hospitalization with that readmission. The analysis of several thousand hospitalizations has allowed the development a screening algorithm for potentially avoidable readmissions. This algorithm has demonstrated excellent sensitivity (detection of virtually all cases problematic).

Also, a study carried out involving 49 US hospitals has allowed to develop and approval of a model adjustment that considers the risks from courses readmission patients according to age, sex, and state of health. As a result of these scientific studies, the National Association for the development of quality in hospitals and clinics (ANQ) has decided to include potentially avoidable readmission rates in monitoring indicators of quality in US hospitals. The ANQ It considered unusual because this index showed different situations between hospitals from the price perspective observed and expected rates based on the characteristics of the patient. The use of a secure algorithm, based entirely on existing medical statistics also avoids a costly collection additional data (Joynt & Jha, 2012). The medical statistics of hospitals US have the added advantage of being able to isolate readmissions placed in third hospitals thanks to the secret code introduced ten years by the Federal Statistical. In this way, a hospital that sees its patients prefer another establishment in the event of complication is treated the same way as a hospital that retains the confidence of the patient readmission (Berenson, Paulus, & Kalman, 2012).

Overview of the Study

Hospital readmissions are very common among patients with cardiovascular diseases in the United States. Various socioeconomic factors have an impact on these readmissions among people 65 years or older (Damiani et al., 2015). The Affordable Care Act has added section 1886(q) to Section 3025 of the Social Security Act to establish the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP). The HRRP involves the Centres for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to moderate reimbursements to inpatient prospective payment system (IPPS) hospitals with excess readmissions effective for discharges beginning on October 1, 2012 (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS], 2016). The principles which apply to this establishment lie in subpart I of 42 CFR part 412 (§412.150 through §412.154).

Nowadays hospital readmissions have particular attention due to the importance of reducing the poor quality of care and the excessive spending that it represents. A 2009 study mentions that close to 20% of Medicare patients are readmitted to the hospital within a 30-day window of their discharge, and this represents an increase up to 17 billion in annual costs to the government the excess (Berenson et al., 2012). The most important factors to avoid rehospitalization include hospital-acquired infections and other complications, premature discharge, failure to coordinate and reconcile medications, poor communication among hospital personnel, patients, caregivers, and community-based clinicians, and poor planning for care transitions (Berenson et al., 2012). Policymakers believe that by reducing readmission rates consequently patient care would be improved and also this would reduce medical expenses.

(Joynt, & Jha, 2012).??? Was erased. Why? The same reference is used every time.

Although some studies agree that hospital readmissions are an important topic for hospitals, they also believe that policymakers’ emphasis on 30-day readmissions is mistaken for three reasons. The first cause, the metric used by hospitals is problematic. This is because only a minimum proportion of hospital readmissions within the 30-day of first discharge are perhaps preventable, and moreover, there are patient and community factors that are outside the control of the hospitals which lead patients back to rehospitalization. Even more, it is not clear that readmissions most of the time represent poor hospital quality. These readmissions could be attributable to low mortality rates or the accessibility to hospital care (Joynt & Jha, 2012). The second reason, for these authors other policies might need attention (that are more imperative) than readmissions. Last reason is, because hospitals are paying a lot of attention to hospital readmissions, they sometimes minimize the importance of other issues related to improving healthcare, such as the safety of the patients. (Joynt & Jha, 2012).

What should be more important in the healthcare industry for the policymakers, health professionals, and the public is providing and receiving better healthcare for the nation at a lower cost.

Research Question

-

Highlight the factors of hospital readmissions and CMS penalties.

Literature Review

Re-Hospitalization in the Medicare Population

Re-hospitalization in the Medicare population may be associated with different factors including failure to understand or to follow physician instructions, reoccurrence of disease, or lack of follow-up care. Moreover, the Medicare population enrollment is expected to grow, and consequently, these readmissions would increase hospital expenses (Miletic et al., & Kaye, 2014). These authors conducted a study to find out if, a telephone intervention/call for help, to reduce the rehospitalization of patients compared to the corresponding control men. After she was placed on the telephone to carry out her patients to the hospital, readmission tightens the analysis of the correct patient data. (Costantino et al., 2013).

The intervention was received by 48,538 Medicare enrollees, and 4504 (9.3%) out of this sample were rehospitalized within 30 days of discharge, as compared to 5598 controls (11.5%, P < 0.0001) (Costantino et al., 2013). The authors/researchers found a direct correlation between the timing of the telephone call/intervention and the rate of re-hospitalization. As a consequence, the closer the patient would receive the phone call to the date of initial discharge, this would result in greater reduction in the number of rehospitalizations. Additionally, in the intervention group, the visits to the emergency room were reduced as compared to controls (8.1% vs. 9.4%, P < 0.0001). The visits to the physician’s office were increased (76.5% vs. 72.3%, P < 0.0001), this suggests that the intervention motivated the enrollees to look for advice to evade readmission. Overall, the total savings of expenses were $499,458 for the enrollees who received the intervention, with $13,964,773 total savings to the healthcare insurance plan (Costantino et al.,

2013). Assisting patients after discharge can help to reduce hospital readmission and expenses.

(Costantino et al. 2013).

The main issue about readmissions is that each year the number of members in Medicare is increasing, and it is crucial for Medicare to try to control health care expenses. It is essential to seek to cut these costs by avoiding readmission after discharge, especially the ones that can be preventable (Costantino et al., 2013). In 2005, the Medicare readmissions reported by the U.S. government had an expenditure of $12 billion, and in 2004 the cost spent on preventable readmission was $17.4 billion (Costantino et al., 2013). The reported estimated current value for re-hospitalizations within 30-day of discharge is $44 billion a year including other patients’ total health care costs. ??

It is considered that most hospital readmissions can be avoidable because it represents the wrong quality of attention and maybe poor transitional care (Costantino et al., 2013). These authors also think that readmissions are due to different factors such as early discharge for the necessity of hospital beds, the lack of follow-up care for discharged patients, the misunderstanding of discharge instructions, and the shortage of help for patients who need continuing care at home (Crockett, 2017). This program is providing telephone support for patients after their discharge, making sure they follow the physician’s instructions and receive enough support from their families. It would help to reduce hospital readmission rates. However, it is valuable to take into consideration future studies to evaluate transitional care costs and utilization (Costantino et at., 2013).

Impact of Social Factors

One of the most important topics taken into consideration for a lot of the studies is the impact of social factors after the patient’s discharge. These variables affect readmissions within the 30-day period because they are outside the hospital spectrum and cannot be controlled. The social factors evaluated for the majority of the CAP studies include the variables race, age, and gender. This study mentions that the worse outcomes are due to the older age of the patients, the result for gender were mixed, and the race more affected is non-White (Faverio et al., 2014).

For heart failure, also older age was significantly related to higher results of patients’ readmissions, but the variable gender showed a mixed result, and the race most affected was also non-Whites, but with a decreased mortality (King et al., 2013). (Calvillo-King et al., 2013).??

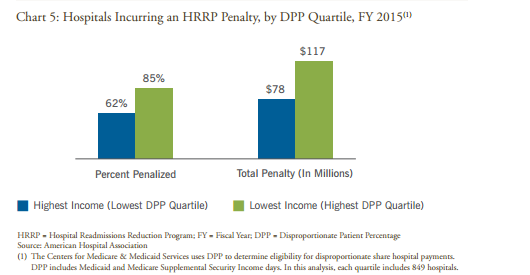

Hospitals that receive a higher amount of low-income patients have a larger possibility to be penalized by the HRRP program (American Hospital Association, 2015).

(American Hospital Association, 2015).

Fiscal Years

In the Fiscal Year (FY) 2012 IPPS final rule the policies stated by the CMS for the hospital readmissions under the HRRP are the definition of readmission. Readmission is admission to a hospital within 30 days of discharge (CMS, 2016). Adopted re-hospitalization measures for these conditions: acute myocardial infarction (AMI), heart failure (HF), and pneumonia (PN). CMS established a method to assess the surplus readmission ratio for each applicable condition which is used in part to calculate the readmission payment adjustment.

The excess hospital for a new system is a measure of hospital performance in the new national average compared to hospital patients with a consistent set of conditions (CMS, 2016). We have established the policy used in the risk adjustment methodology approved by the National Quality Forum (MNC)?? (NQF) System for excess readmission reasons, which includes an adjustment that we can film are certain patient characteristics of Demographics, comorbidities, and patients.

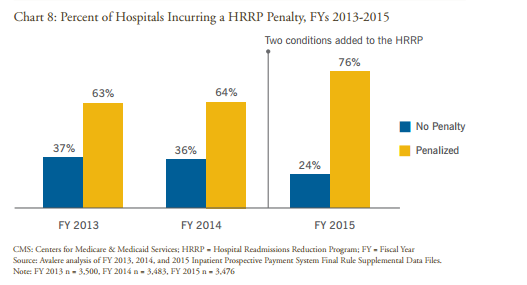

Additionally, the increase of new terms added to the HRRP program in the Fiscal Years 2013-2015 augmented the percentage of hospitals penalized in the United States.

(American Hospital Association, 2015)

These hospitals had an increment in rehospitalizations, due to the increase of additional conditions such as total hip and knee replacement.

Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP)

The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) is one of the payment initiatives executed after the enactment of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA). This program is in charge of fining hospitals through a Medicare reimbursement rate cuts of 1% when they have higher patients’ re-hospitalization in the first year of the causes of heart attack, pneumonia, or congestive heart failure (Costantino et al., 2013). If by the third year, hospital readmissions do not improve, an extra 2% reduction will be added. Another study also mentions that in the United States, among the patients enrolled in Medicare fee-for-service who were discharged from a hospital, 19.6% were readmitted to a hospital within 30 days (Damiani et al., 2015).

There is another study that mentions the addition of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in October 2014, to HHRP by the U.S. CMS and also the addition of acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) (Feemster & Au, 2014). This is with the objective of encouraging hospital quality and decreasing expenses by generating monetary incentives for hospitals to avoid readmissions (Feemster & Au, 2014). These authors also mention that in the U.S. more than 2,000 hospitals have been fined up to date. This results in approximately $280 million dollars for the fiscal year of 2013 (Feemster & Au, 2014).

CMS expanded the conditions to add all-cause unintended rehospitalizations for AECOPD in October 2014. COPD is an important disease to measure for readmissions because in the U. S. It represents more than 1.5 million visits to the emergency room and 725,000 patients’ entries into the hospital/hospital. The interventions per year represent health care expenses up to $60 billion for the U. S. annually (Feemster & Au, 2014). About 34 to 40% of AECOPD hospitalized patients did not get suggested treatments while approximately half of the patients had at least one incorrect or potentially dangerous treatment (Feemster & Au, 2014).

The number of patients with AECOPD who are rehospitalized after discharge within 30-day is nearly 22.6% with an all-cause which states the importance for patients, hospitals, and payers (Feemster & Au, 2014). Hospitals measure readmissions by assessing administrative data and claims data. The social factors showed (somehow) influence on AECOPD patients’ readmission rates of 22% greater in patients living in low socioeconomic areas and higher among black patients in comparison with other races or ethnicity groups (Feemster & Au, 2014). In the fiscal year 2012, more than 3000 hospitals were penalized/punished with high penalties. There is a noticeable big proportion of COPD patients with low-income status. CMS should try to give extra support and funds to hospitals to help patients welfare in their transition from the hospital to their houses through the Community-based Care Transition Program (Berenson et al., 2012). Approximately/Nearly 33% of 1,904,640 deaths among persons 65 years and older in the U. S. died in a hospital in 2013, although most of these Medicare enrollees would prefer to die in their homes (Gorina et al., 2015). The rate of patients who died after their hospitalization in a hospital for pneumonia causes was 12.1% within their first 30 days of hospitalization. (Gorina et al., 2015). Was missing/added back.

Close to 1 in 5 patients enrolled in Medicare fee-for-service who were discharged f from a healthcare institution were readmitted within 30 days (Hansen, Young, Hinami, Leung, & Williams, 2011). There is a study that compares three different data collection methods, to evaluate unplanned readmissions among patients who had colorectal surgery from July 2009 to November 2011. The type of methods used was the NSQIP clinical reviewer method, the physician medical record review, and the University HealthSystem Consortium (UHC) administrative billing data method (Hechenbleikner et al., 2013).

They found 735 patients who had colorectal surgery and were readmitted to the hospital. While the NSQIP method identified 14.6% (107 readmitted patients) on the other hand, UHC found 17.6% (129 readmitted patients) out of the 735 found (Hechenbleikner et al., 2013). Associated with index admission the NSQIP detected 72% rehospitalizations and the physician chart review 83% (Hechenblaikner et al., 2013). The UHC method noted that 51% of rehospitalizations were associated with index admission and a physician chart review found 86% (Hechenbleikner et al., 2013). Noticing the significant discrepancy among each method is important. According to the UHC method, 66 out of those 129 readmissions (51%) were considered preventable. On the contrary, the physician chart review 112 of 129 rehospitalizations (87%) were found to be needed when the patient returned to the hospital (Hechenbleikner et al., 2013).

These methods showed that most of the readmissions were attributable to surgical site infections (46 of 129) which represent 36% and dehydration conditions 30 out of 129 (23%). (Hechenbleikner et al., 2013). Out of 41 patients, 129 (31.8%) who presented some complications, but had good care after discharge did not need readmission (Hechenbleikner et al., 2013). This study suggests that results on readmission rates also depend on what type of method is used to evaluate readmissions. Sometimes they get different outcomes, and these results can affect hospitals’ penalizations (Hechenbleikner et al., 2013).

This type of study reflects the necessity for hospitals or healthcare organizations to find better ways to collect data to have accurate information about patient readmissions and prove to CMS the correct number at the time of an audit. Having all this information in a file or an archive or software or program will help to identify the real readmissions and avoid being perverse penalized (Berenson, 2012).

The CMS determined a projected number of readmissions for all the hospitals in the U. S. These readmission rates were for pneumonia, acute myocardial infarction, and congestive heart failure from July 2008 to June 2011 (Joynt & Jha, 2013a). The CMS also adopted these readmission rates to sex, age, and coexisting conditions. The CMS examined the expected readmission rates for each hospital, and the hospitals that exceeded these rates were penalized.

CMS reported that close to 66% of the hospitals in the U. S. received penalties of up to 1% of their reimbursement for Medicare members (Joynt & Jha, 2013a). By 2015, CMS will expand the penalties to 3%, and by 2013, CMS is predicted to recover $280 million from the 2217 total penalized hospitals. From the entire hospitals that were penalized (2217).

There is considerable controversy regarding hospital penalizations due to high readmission rates. There are two main reasons why this policy is debatable. The first one is why hospitals are responsible for rehospitalizations, if when patients are discharged from the hospital following discharge physician instructions, taking medication, and the continuum of care depends totally on the patients. And the second point of contention is the different type of measures to evaluate hospital readmission rates (Burke & Coleman, 2013).

Two groups of patients are more susceptible to hospital readmissions: those who have a severe illness, and the ones that lack post-discharged care due to a low socioeconomic status (Joynt & Jha, 2013a). The way measures evaluate readmissions is not reasonable because they do not take into consideration the complexity of a disease, or disability of each patient. Instead, they measure everything as socioeconomic factors creating a significant disadvantage for the hospitals that care for a considerable number of patients with the most severe illnesses and with a poor socioeconomic status at risk of criminal penalties. ??

There are two circumstances that maybe hospitals are playing out the system, the first one the HRRP has invested in activities and programs to prevent hospital readmissions, and there was a decrease in hospital readmissions from 2009 15.5% to 15.3% in 2011 (Joynt & Jha, 2013a). It would be beneficial that these efforts of reducing rehospitalizations would be real, and not just some hospitals were playing the system and admitting patients to the emergency room or observation areas.

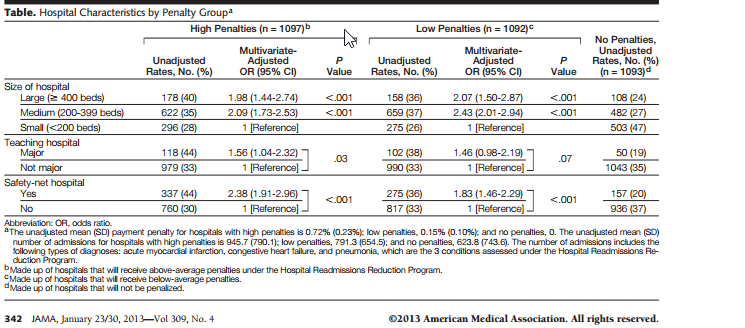

This is a higher number than what CMS expected. It is now important to emphasize that there is evidence that safety-net hospitals, as well as teaching hospitals, are highly penalized by the HRRP (Joynt & Jha, 2013a).

(Joynt & Jha, 2013a).

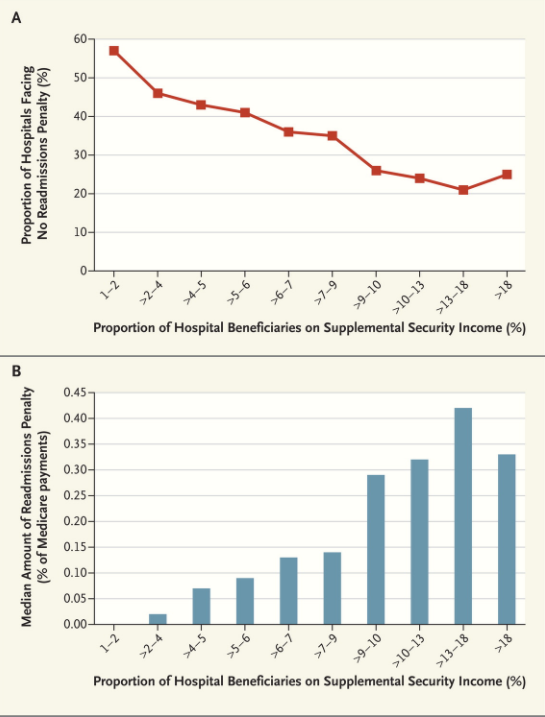

The proportion of hospitals is not against the Readmission Penalty (Panel A) and an average amount of Penalty (panel B), according to the proportion of hospital patients receiving Supplemental Security Income. Medicare Payments Advisory Committee is given.

Having these two visions in consideration, we can deduce that other actions would be worthy to do, to maintain the gains that have been accomplished while preventing severe penalizations to hospitals that serve underserved patients.?? First, readmission rates need to be adjusted to socioeconomic factors so this would permit a fair game between safety-net hospitals and non-safety net hospitals to achieve similar re-admission rates, and this will permit that safety-net hospitals would not be penalized when they treat an additional quantity of sick patients.??

Second, it would be crucial for the HHRP to implement penalties according to the timing of the readmission. Readmissions that happened during the first days of the discharge might reveal the patient had inadequate post-discharge care or did not follow the instructions appropriately, whereas readmissions that occurred four weeks later after the initial release reflects the severity of the patient’s illness (Joynt & Jha, 2013a). Moreover, when rehospitalization occurs three hours or three days after discharge, it could represent to be weighed worse by the algorithm than 30-day readmission.??

For this reason, it would be worthy for hospitals that care for a significant number of patients with socioeconomic problems and with severe diseases to coordinate and plan after discharge care to avoid short-term rehospitalizations to prevent being penalized due to these patient factors. Lastly, giving incentives to hospitals for low mortality rates would compensate for the risks that hospitals face for readmissions. This means that low mortality rates/hospital death rates would be taken into consideration in the readmissions metrics, instead of penalizing hospitals for keeping their patients with severe diseases alive, even with readmissions but showing low mortality rates (Joynt, & Jha, 2013a). In this case, this represents that large teaching hospitals are more at risk of being penalized for their high readmission rates but low mortality rates, on the other hand under the CMS hospitals with low readmission rates do better even though they reflect high mortality rates.?? These authors suggest that one technique to associate these two results is to evaluate the patients’ 30 days after discharge, keeping in mind the days the patients are alive and (out) not in the hospital. (Joynt & Jha, 2013a). Erased

Similarly, the same authors Joynt and Jha found in another study that certainly, large teaching hospitals and safety-net hospitals (SNHs) are more vulnerable to being penalized by the HRRP. (Joynt & Jha. 2013b).Erased

(Joynt & Jha, 2013b).

Policies should be changing and adapting to the needs of the public and organizations. Penalization by HRRP of the hospitals that care for the most vulnerable patients and with socioeconomic disadvantages could change if HRRP changed the metrics. It will give incentives or change some guidelines that would help hospitals that have the poorest patients in the U. S. and provide programs that would improve coordination of care for patients after discharge from the hospital and during their recovery at home. These events occur outside of the hospitals’ walls, but with a proper coordination plan for discharged patients, hospitals would be less hurt by the HHRP penalizations.

Methodology

Research Design

The study design that has been used to conduct the research is the inductive approach, as there has been a lot of research on health readmission and how it can be reduced. However, this research focuses on hospital readmissions and CMS penalties. The inductive study refers to the design which has been taken from the previous research, but it is being explored in a new direction. After recovery from a serious illness, some patients are susceptible to new complications, many of which require readmission to the unit of therapy Intensive care unit (ICU). This is associated with increased mortality and longer stay. in the hospital. Early identification of patients at risk of readmission. The ICU can facilitate the appropriate allocation of resources to prevent morbidity and mortality.

Research Approach

A qualitative research approach will be used to conduct the research study. Does qualitative research help to focus the issue is? to examine the humanist? approach, in which different parts are similar, beliefs, customs, beliefs, and emotions too? people (Tsai et al., 2013).

Data Collection

Data will be collected from secondary sources such as the internet, published papers, articles, and online libraries. 30 articles have been selected from 900 studies as these materials fulfill the inclusion criteria that are required for the research.

| CRITERIA | INCLUSION | EXCLUSION |

| From 900 articles | 800 articles were excluded because of their title and abstract. | |

| 50 articles | Were excluded for more detailed reading. | |

| 40 articles | Were selected for full-text review. | |

| 30 articles | Were selected because they meet the inclusion criteria. |

Data Analysis

The search was conducted from electronic databases from January 1, 2006, to August 22, 2016. Studies with association with reduce readmissions, socioeconomic factors, elderly patients, and CMS penalties in hospitals in the United States were included.

Sources of Information

Google Scholar eBook libraries are the primary sources of data. Keywords that have been used are Elderly, Readmissions, Heart Failure, social factors, Medicare, Medicaid, and penalties.

Results

Readmission is considered potentially avoidable if not it was scheduled at discharge from the previous hospitalization if it is caused by at least an affection already known at the time off and if the discharge occurs within thirty days. The readmissions related to transplants, parts, chemotherapy, radiotherapy or surgical intervention following a hospital stay for medical appointments are examples considered envisaged. The readmissions for a new condition that is not present at the time of the previous hospitalization are considered inevitable. The “potentially preventable” means that, in the case ideal, it is not expected at the date of a readmission discharge. So this is an undesired event, whose causes can be manifold. The algorithm identifies readmissions unwanted, as demonstrated by the sensitivity (96%) and specificity (96%) of identification, but that does not mean that all readmissions can be avoided, which is why it is analyzed critically if they occur too frequently and find out the causes. The 30 days is usually indicated by the literature science, and it has been confirmed by the study conducted on the data US.

Determination of the Population at Risk

The potential readmission population includes all patients hospitalized and discharged alive, not transferred to another hospital, and 3 US residents. The analysis of data showed that the US measurement of readmission rates could be altered by the inclusion or exclusion of hospitalizations for surgeries it could also be performed on an outpatient basis. Because these interventions are frequent in some hospitals and rare in others (from 4% to 30% of planned surgery), they were excluded from the calculation. For the same reason, they have also banned shelters for sleep apnea. Residents abroad patients are also excluded since it runs the risk of being readmitted to another country, which would distort the comparisons between hospitals. Infants are excluded because the readmission indicator aims to judge the quality of preparation for the discharge of patient’s sick people. The extent of the readmission rate takes into account the time elapsed after the patient’s discharge. As a result, a patient reinstated in the same or another hospital is no longer at risk of being restored, resulting in a time of censorship exposure to risk. Each readmission is at risk of being followed by another readmission.

Calculation of the Adjusted Readmission Rate

The danger of being readmitted, so it is potentially preventable calculated from a Poisson regression model to consider the time of exposure to the risk of readmission. The variables used are the affections and operations of patients, age, and sex, the admission (emergency or not), as well as the presence of a hospital stay during the six months previous.

For calculating the expected readmission rates as a function of cases in 262 hospitals, more than 3.2 million withdrawals were used by US hospitals between December 1, 2003, and November 30, 2007 (Tsai et al., 2013). The hospital data whose coding quality was questionable were discarded. Clinical categories in question originate from the system SQLape® classification, which considers all the affections and operations presented by patients, regardless of their rank (primary or secondary). SQLape is a software that is used by hospitals for patient quality and cost management. Some categories are associated with low risk (obstetrics, ENT infections, skin diseases), and other high risks of type operative (amputations, transplants, coronary bypass, major interventions to the digestive tract, etc.). The diagnostic type, mainly chronic diseases, recurrent or malignant: tumors, agranulocytosis, ischemic disease, cirrhosis, failure respiratory, mental illness (depression, schizophrenia, drug addiction, and anorexia nervosa) (Merkow et al., 2015). A patient who has Malignant cancer, anorexia, or chronic renal insufficiency presents risks around ten times higher. These are often comorbid, with no connection to the diagnosis Main, which explains why they cannot be used DRG grouper to fix this type of risk. Even indexes comorbidity (were taken for example Charlson) into consideration, as poorly predictive (few categories diagnostic, no operative criterion). Since the model predictive presents statistical uncertainties, it was given the 95% confidence interval for defining the minimum adjusted rates and max (Nedza et al., 2016). (Nedza, Fry, DesHarnais, Spencer, & Yep, 2016).???

On a practical level, we calculate the adjusted rate of readmission was multiplying the average rate observed in Switzerland by the relationship between the observed and expected rates of each hospital. The following example illustrates the procedure (Rau, 2014). Rate observed globally in Switzerland: 5% Rate observed hospital H: 6% Expected rate Hospital H: 4% Adjusted hospital readmission rate H: 7.5% (= 5% 6% / 4%). This procedure has the advantage of considering the objective of each hospital to judge its performance as a function of patients that welcomes and allows to compare the values of the hospitals using the adjusted rate. In our example, the rate adjusted is higher than the rate observed, which allows considering the fact that the patients admitted to the hospital question had a lower risk of being readmitted compared to those of other hospitals (Shah et al., 2014). (Shah, Churpek, Coca, & Konetzka, 2014).??

Discussion

Ideally, an indicator must meet some requirements: utility, accuracy, the absence of distortions, interest, precision, reliability, and reproducibility, cost, comparability, availability. Reducing the number of potentially avoidable readmissions is useful to lower costs and improve patient safety. The indicator accuracy is ensured by an excellent sensitivity and specificity of misguided cases (numerator) and a definition Strict the population at risk (denominator). The absence of distortion is ensured by excluding hospitalizations for interventions Surgical that could also be carried out by outpatients and hospitals including readmissions in third. The conflicting results between hospitals, regarding rates observed and the expected rate, demonstrate the interest indicator. The confidence intervals were calculated from SQLape® sufficiently tight to highlight differences significant between hospitals. The quality of the encoding is examined with the instrument to sidetrack any reliability problems. The tool is based on data routinely available in all hospitals, which allows for limiting the cost of production indicator (Swinburne, et al. 2017).

The calculation of expected interest rates considers all information available on patients’ health status to ensure comparability between hospitals. To avoid misinterpretation, users should find two system limits. The first is linked to the waiting time for having the results, given that the absolute values come shortly after more than a year. The calculation takes account of readmissions to hospitals third. This means that the data collected by the Federal Statistical must be complete and validated. An interim rate can be determined from the hospital by installing the tool internally, but it is necessary to estimate the rate of external readmissions, it is made by observations of the year previous. The second limitation is due to the difficulty of documenting the causes of readmission. About a quarter of potentially avoidable readmissions can be attributed to problems whose responsibility is to hospitals, for example, surgical complications, side effects of medications, and resignation premature. Half of the readmissions are tied to difficulties handling the situation on an outpatient basis. These can be problems regarding the shortage of care after a hospitalization, a patient’s inappropriate behavior or the aggravation of disease that in some cases could have been avoided with a better organization of outpatient follow-up care (Tsai et al., 2013).

Finally, another quarter of readmissions is caused by spontaneous evolution disease; it is not possible to identify errors in the care provided. It should be emphasized that the reasonable rate considers these situations and we cannot expect that a hospital does not have potentially avoidable readmissions. The instrument’s interest is to isolate readmissions suspicious, without forcing hospitals to see them all. A rate adjusted little is reassuring and a detailed analysis can then it is focused on hospitals or services with excessively high levels.

The extent of potentially avoidable readmission rates can be distorted if the quality of hospital medical statistics is insufficient. The data quality requirements are concerned with completeness, accuracy, and compliance with the coding of diagnosis, of operations, and administrative data (mode of admissions, days of operation, etc.). If data quality appears suspicious, for example, if the patient numbers are not the same from one year, a warning is issued. The quality of the data is evaluated in Excel tables, which allows a good check that the format of the data provided to SQLape® is consistent and correct if necessary. Self the data provided are identical, although the results should, therefore, be equal.

The analyses carried out in Switzerland have demonstrated so far that almost 50% of readmissions were linked to relapse or aggravation of disease already present at the time of admission. These disorders were often comorbidities they had not justified the previous hospitalization. Typically, such readmissions cannot be attributed to only one hospital, which only had an indirect influence on an outpatient who was taking charge of patients, but it is still worthwhile to insist on accountability, albeit partial, that is up to the hospital. Care outpatient subsequent are often guaranteed by doctor’s hospitals (e.g. surgeons and oncologists) or polyclinic hospitals. On the other hand, the hospital is obliged to arrange subsequent treatment outpatient, for example by taking the first appointment with the doctor, sending timely necessary information, and providing services immediately the requested address.

Experience shows that staff nursing hospital has little contact with services at home, which often take over late, particularly when the patients are discharged over the weekend. Sometimes, the readmission is because the patient did not follow the recommendations or has not understood; even in these cases, the hospital can help to improve the situation by improving information to the patient or family. A quarter of potentially avoidable readmissions is due to the evolution of the disease after the patient’s discharge despite the fact that treatment was optimal. Unfortunately, it is not possible to isolate these cases, which make up an interference factor in starting from the medical statistics data. It must, however, be remembered the expected rates of patients consider the health, and then hospitals should not be penalized.

The analysis of the causes of readmissions is possible if the patient is returned to the same hospital, but it is obviously more complicated when he or she was admitted to another hospital. Respect the confidentiality prevents hospital readmission and communicating the patient’s name to the first hospital. Requesting permission from the patients at the time of their discharge is not an adequate solution because the patient has the right to keep for themselves the reasons for dissatisfaction if they prefer to be readmitted elsewhere. If a hospital is compared with a high rate of readmissions of his patients to other hospitals and a rate Global too high, it is advisable to rely on an auditor doctor exterior will not reveal the names of the readmitted patients. In this case, you might find a solution to assign a unique patient number to the hospitals in question

CMS’ Hospital Readmission Penalties Worked Under Affordable Care Act

Medicare began using a new tactic to get hospitals to reduce costly, unnecessary readmissions. The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, established in the 2010 Affordable Care Act, allows the CMS to withhold inpatient prospective payments to short-term acute hospitals with excessive readmissions for certain conditions. Since then, the debate has ensued over whether the program is effective at improving hospitals’ quality of care (Fontanarosa & McNutt, 2013).

Opponents cite concerns about unintended consequences and criminal penalties for institutions that serve sicker patients, while the government maintains that its efforts have borne fruit. A new study, published Monday in the Annals of Internal Medicine, concluded that hospital readmissions across the U.S. indeed declined to start with the ACA and that moreover, hospitals with the highest readmission rates before 2010 improved the most in the years following.

There’s been gradual, continuous, graded attention devoted to the issue of readmissions (Herrin et al., 2014). Although it would not be possible to disentangle what the various forces of financial penalties, public reporting, extra attention to readmissions — and their specific contributions to reduced readmissions, the study showed that financially incentivizing reduced readmissions leads to reduced readmissions (Kangovi & Grande, 2011).

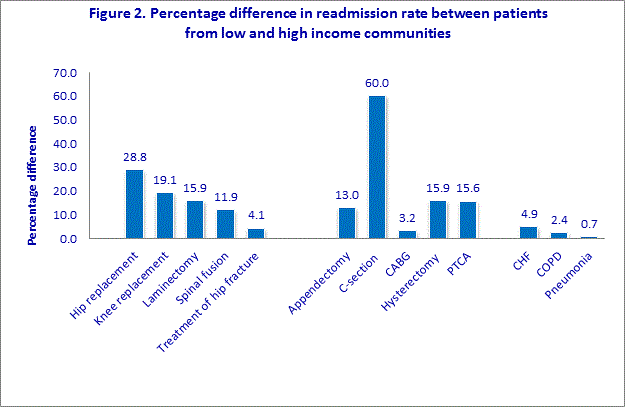

Figure 1 Percentage Difference In Re-Admission Rates Between High And Low Communities (Kansagara et al., 2011)

The main course was found a large reduction in rates followed the new law is a law and regulation trends in the opinion of the more low-performing hospitals. The researchers looked at the records of more than 15 million fee-for-service Medicare patients discharged from 2,868 acute-care hospitals for heart attacks, congestive heart failure, or pneumonia from 2000 to 2013. They calculated risk-standardized readmission rates and categorized hospitals into four categories of performance: highest, average, low, and lowest. Although overall readmissions fell after 2010 — the post-law period, lower performing groups made greater gains. Risk-standardized readmissions dropped by 69 and 74.5 per 10,000 discharges annually among the highest and average-performing groups (Kansagara et al., 2011).

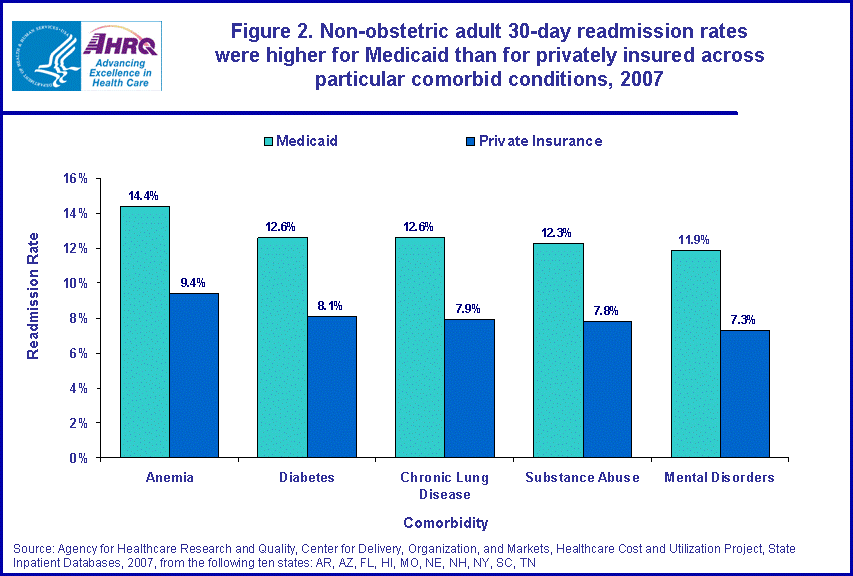

Figure 2: Lowest Rate Of Readmissions In The U.S. (Kripalani, Theobald, Anctil, & Vasilevskis, 2013)

Among the small and lowest performing groups, they dropped by 83.2 and 92.4 per 10,000 discharges, respectively. In other words, those hospitals that were financially penalized the most improved the most. Although readmissions penalties did not kick in until October 2012, the researchers counted the first quarter of 2010, when President Barack Obama signed the ACA, as the intervention (Kripalani, et al. 2013). (Kripalani, Theobald, Anctil, & Vasilevskis, 2013).

The fact that hospitals became aware of looming penalties in 2010 and began redesigning care in anticipation of them justified that decision, the authors wrote in the study. These findings come on the heels of an allowance granted to safety net hospitals in a section of the 21st Century Cures Act, signed into law in mid-December, which adjusts the risk of hospital readmissions penalties based on the patient mix. Now, when fines are calculated, hospitals that treat higher proportions of poorer, sicker patients will be compared to like institutions, rather than against those that treat healthier, well-to-do patients (Krumholz et al., 2013). Stephen Soumerai, who teaches population medicine at Harvard Medical School and was not involved in and had not seen the study, cautioned against extrapolating from it that health outcomes had improved as a result of reduced readmissions.

Conclusion

In some cases, the cause can be deduced with the sole statistical Medical, where appropriate through computer help. In other situations, a letter is necessary to analyze the discharge of readmission which usually gives the reason why the patient was hospitalized again. Finally, a point medically it is sometimes necessary to decree whether treatment outpatient was appropriate and whether better-informed outpatient doctors could afford to avoid readmission. Experience shows that in general the causes of readmission have changed from when hospitals have standard rates. In these cases, it is not always easy to take measures for improvement. Conversely, when rates are too high, the reasons for readmissions focus on a small number of cases that you can access. The purpose is not to lead to zero potentially avoidable readmissions. That would presuppose a substantial increase in resources to ensure discharge in the best conditions, which would generate considerable costs and it is to the detriment of other aspects of quality (Joynt & Jha, 2012).

Whereas the examination of medical records is relatively expensive, it is recommended to aim the analysis of the services where the readmissions are too numerous. If interest rates are high in all services, it may want to examine a random sample of wrappers of the identified readmissions. If you suspect an excessive number of early resignations, could be interesting to see if readmissions are associated with shorter stays (adjusted according to the severity of the case). If readmission rates are consistently too high, you advisable to follow them on a quarterly basis asking doctors responsible for systematically documenting the causes of identified readmissions.

Being recently viewed patients, doctors can quickly expose their interpretation of the reason for readmission without first carrying out long wrappings exams. The data provided in SQLape® must understand the data from 1st June of the previous year up to 30 days after the last analyzed hospital discharge.

It can calculate the observed and expected rates for distinct periods from detailed results for hospitalization files. Practical recommendations depend on the results rate observed below the expected rate: congratulate the team caring for patients. A review of records clinics is always possible to understand the operation of the tool, but they hardly stand to measure improving effectiveness. Rate observed higher than expected rate but lower than the rate expected maximum (typical). The results were analyzed for each service to isolate those with excessively high levels. They could benefit from a review of medical records, the rate observed for the first time was higher than the average rate maximum, and conduct a review of medical records. Possibly excluding services with average rates and a test at the random sample, if it is a critical hospital dimension analyze the causes of readmissions to find out if it comes to particular problems of certain services. The specific diseases and whether the adoption of standard measures for several services would reduce the rates. (Chakraborty et al., 2011).

Rates observed at higher than the expected rate shooting Maximum: perform quarterly analysis as soon as the Medical statistics are complete and transmit to the doctor responsible for the data of his patients asked him to assign the most likely cause of readmission. This procedure requires an organizational effort, but it can be more rapid than a review of historical medical records. It should be remembered that the standard rates are calculated independently of whether the readmissions take place at the same hospital or not. It is, therefore, necessary to correct the observed rate based gross the data to compare the expected rate. The software used by the hospital for internal analysis is the same and should, therefore, provide the same results for rates interior observed and single cases. For the calculation of rates of readmission proves correct, it is essential that the number of patients is the same regardless of the year in question. The speed external observed is higher because it takes into account all US hospitals in which patients may have been readmitted. Even the observed rate may be slightly high, for considering the admissions in the previous six months all US hospitals (Sosunov et al., 2016).

Recommendations

There are several possible measures to reduce the number of potentially avoidable readmissions if their causes are known. According to scientific literature, the side effects of drugs represent three-quarters of the accidents that occur the month following the resignation (Chakraborty et al., 2016). The readmissions caused by these accidents are rare, but half of the cases are due to medication errors, for example, interactions of medication, and inadequate surveillance of a treatment anticoagulant.?? Some preventive measures for patients at high risk (multiple drugs, antibiotics, glucocorticoids, anticoagulants, antiepileptics, and hypoglycemic agents) have proven useful (Chakraborty et al., 2016). Surgical complications could be too frequent due to a multitude of possible causes: indications and techniques questionable surgical, infection prevention measures poor skills or training to improve the team, etc. An analysis of the profile of the readmitted patients would well ensure that the operations carried out to correspond to the mandated hospital. It is normal that sometimes occur readmissions of this kind, but these situations should remain below the expected rate, always considering the diseases suffered by patients.

There may also be other complications, such as thrombosis or embolisms. If they are too numerous, one may wonder whether are adequate preventive measures taken. The discharge procedure is certainly a point of critical transition (Chakraborty et al., 2016). The communication between the hospital and service patients is often insufficient. Several studies have demonstrated the frequent omission of relevant information for the following patient care, including the results of recent tests and planning of follow-up. It is established that the planning of outpatient appointments decreases the risk of readmission (Chakraborty et al., 2016).

Some authors have proposed a list of control for the discharge procedure, but its effectiveness is not studied. So far, US hospitals have found few early resignations, but if these situations become frequent, primary doctors should be warned and more involved in decisions concerning the departure and in their organization.

In general, good cooperation between hospital physicians, their outpatient colleagues, staff nurses, patients, and family members helps to ensure that the discharge is well prepared. It happens, however, that this process is overlooked, for example, if the hospital is overloaded (rate always very high occupancy) or if doctors are regularly under pressure to the emergency room admissions. In the latter case, especially if patients are elderly and suffer from more diseases, it would be appropriate to provide a unit that is responsible for managing the resignation (Chakraborty et al., 2016).

References

American Hospital Association. (2015). Trendwatch. Rethinking the Hospital Readmissions

Reduction Program. Retrieved from http://www.aha.org/research/reports/tw/15mar-tw-readmissions.pdf

Berenson, R. A., Paulus, R. A., & Kalman, N. S. (2012). Medicare’s Readmissions-Reduction Program – A Positive Alternative. The New England Journal of Medicine. Retrieved from

http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp1201268#t=article

Burke, R. E., & Coleman, E. A. (2013). Interventions to decrease hospital readmissions keys for cost-effectiveness. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 173(8), 695-698, doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.171

Calvillo-King, L., Arnold, D., Eubank, K. J., Lo. M., Yunyongying, P., Stieglitz, H., & Halm, E. (2013). The impact of social factors on risk of readmission or mortality in pneumonia and heart failure: Systematic review. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 28(2), 269-282. doi:10.1007/s11606-012-2235-x

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS]. (2016) Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP). Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/acuteinpatientpps/readmissions-reduction-program.html

Chakraborty, A., Selby, D., Gardiner, K., Myers, J., Moravan, V., & Wright, F. (2011). Malignant bowel obstruction: the natural history of a heterogeneous patient population followed prospectively over two years. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 41(2), 412-420. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.05.007.

Chakraborty, H., Axon, R. N., Brittingham, J., Lyons, G. R., Cole, L., & Turley, C. B. (2016). Differences in hospital readmission risk across all payer groups in South Carolina. Health Services Research. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/ 308738412_Differences_in_Hospital_Readmission_Risk_across_All_Payer_Groups_in_South_Carolina. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12579

Constantino, M. E., Frey, B., Hall, B., & Painter, P. (2013). The Influence of a Postdischarge Intervention on Reducing Hospital Readmissions in a Medicare Population. Population Health Management, 16(5), 310-316. doi:10.1089/pop.2012.0084

Damiani, G., Salvatori, E., Silvestrini, G., Ivanova, I., Bojovic, L., Iodice, L., & Ricciardi, W.(2015). Influence of socioeconomic factors on hospital readmissions for heart failure and acute myocardial infarction in patients 65 years and older: Evidence from a systematic review. Dove Medical Press, 10, 237-245. doi:10.2147/CIA.S71165

Faverio, P., Aliberti, S., Bellelli, G., Suigo, G., Lonni, S., Pesci, A., & Restrepo, M. I. (2014). The management of community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly. European Journal of Internal Medicine, 25(4), 312-319. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2013.12.001

Feemster, L. & Au, D. H. (2014). Penalizing hospitals for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease readmissions. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 189(6), 634-639. doi:10.1164/rccm.201308-1541PP

Fontanarosa, P., & McNutt, R. A. (2013). Revisiting hospital readmissions. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 309(4), 398-400. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.42

Girona, Y., Pratt, L. A., Kramarow, E. A., & Elgaddal, N. (2015). Hospitalization, readmission, and death experience of noninstitutionalized Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries aged 65 and over. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 84, 1-23. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr084.pdf

Hansen, L. O., Young, R. S., Hinami, K., Leung, A., & Williams, M. V. (2011). Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: A systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine, 155(8), 520-528. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00008.

Hechenbleikner, E. M., Makary, M. A., Samarov, D. V., Bennett, J. L., Gearhart, S. L., Efron, J. E., & Wick, E. C. (2013). Hospital readmission by the method of data collection. Journal of the American College of Surgeon, 216(6), 1150-1158. doi.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.jamcollsur.2013.01.057

Herrin, J., St. Andre, J., Kenward, K., Joshi, M. S., Audet, A-M., & Hines, S. C. (2014). Community Factors and Hospital Readmission Rates. Wiley Online Library. 50 (1), 20-39. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12177

Joynt, K. E., & Jha, A. K. (2012). Thirty-Day Readmissions – Truth and Consequences. New England Journal of Medicine. 366, 1366-1369. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1201598

Joynt, K. E., & Jha, A. K. (2013a). A Path Forward on Medicare Readmissions. New England Journal of Medicine. 368, 1175-1177. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1300122

Joynt, K. E., & Jha, A. K. (2013b). Characteristics of Hospitals Receiving Penalties under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 309(4), 342-343. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.94856

Kangovi, S., & Grande, D. (2011). Hospital readmissions – not just a measure of quality. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 306(15), 1688-1698. doi:10.1001/jama.20111515m

Kansagara, D., Englander, H., Salanitro, A., Kagen, D., Theobald, C., Freeman, M., & Kripalani, S. (2011). Risk prediction models for hospital readmission. A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Association, 306(15):1688-1698. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.1515

Kripalani, S., Theobald, C. N., Anctil, B., & Vasilevskis, E. E. (2013). Reducing hospital readmission: Current strategies and future directions. The National Center for Biotechnology Information, 65, 471-485. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-022613-09041

Krumholz, H. M., Lin, Z., Keenan, P. S., Chen, J., Ross, J. S., Drye, E. E.,…Normand, S. L. (2013). The relationship between hospital readmission and mortality rates for patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, or pneumonia. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 306(16), 1796-1797. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1562

Merkow, R. P., Ju, M. H., Chung, J. W., Hall, B. L. Cohen, M. E., Williams, M. V.,…Bilimoria, K. Y. (2015). Underlying reasons associated with hospital readmission following surgery in the United States. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 306(16), 1796-1797. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1562

Miletic, K. G., Taylor, T. N., Martin, E. T., Vaidya, R., & Kaye, K. S. (2014). Readmissions after diagnosis of surgical site infection following knee and hip arthroplasty. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 35(02), 152-157.

Nedza, S., Fry, D. E., DesHarnais, S., Spencer, E., & Yep, P. (2016). Emergency department visits following joint replacement surgery in an era of mandatory bundled payments. Academic Emergency Medicine.

Rau, J. (2014). Medicare fines 2,610 hospitals in the third round of readmission penalties. Kaiser Health News Retrieved from http://khn.org/news/medicare-readmissions-penalties-2015/

Shah, T., Churpek, M. M., Coca, P. M., & Konetzka, R. T. (2014). Understanding why patients with COPD get readmitted. Journal Publications Chestnut, 147(5), 1219-1226. Retrieved from http://journal.publications.chestnet.org/

Sosunov, E. A., Egorova, N. N., Lin, H. M., McCardle, K., Sharma, V., Gelijns, A. C., & Moskowitz, A. J. (2016). The impact of hospital size on CMS hospital profiling. Medical care, 54(4), 373-379.

Swinburne, M., Garfield, K., & Wasserman, A. R. (2017). Reducing hospital readmissions: addressing the impact of food security and nutrition. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 45(1_suppl), 86-89.

Tsai, T. C., Joynt, O., Gawande, A. A. & Jha, A. K. (2013). Variation in surgical readmission rates and quality of hospital care. New England Journal of Medicine, 369,1134-1142 doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1303118