Scenario: You’re Hired! In two weeks, you will be stepping in to open a new toddler room that practices developmentally appropriate instructional practices (DAP) for toddlers. You will have five students with the youngest student just turning 1 and the oldest student about to turn 2. This assignment is broken down into three steps:

Step 1: How will you set up your room? a. Draw a map of your toddler room set up. Label the map with information about how you set up the room. (See Rubric) b. Make a list of the toys/materials will you need to have in your classroom that are developmentally appropriate for toddlers. (See Rubric) c. Write a 1000 word reflection about the decisions you made to set up your DAP classroom and the items you selected to include in your classroom with citations. (See Rubric).

Step 2: What will your schedule include? a. Make a daily developmentally appropriate schedule for your toddlers’ day. (See Rubric) b. Write a 1000 refection about what you included in your daily schedule and why you included those practices and activities with citations. (See Rubric)

Step 3: Learning Environment Write a reflection with citations about the developmentally appropriate learning environment you will be creating in your toddler room to help your toddlers grow and develop. What have you decided to do with your learning environment? why have you decided to include these practices in the learning environment? how will you create the DAP learning environment? What are the results you are hoping to create in this DAP learning environment? (See Rubric)

Introduction

This report comprehends the design and setting setup of a developmentally appropriate environment for toddlers, combining a creative room set time-framed schedule and a caring learning environment. Stressing safety, discovery, and total development, it guides the development of a valuable educational experience.

Part 1: Room Setup

Map and Description of Toddler Room Setup

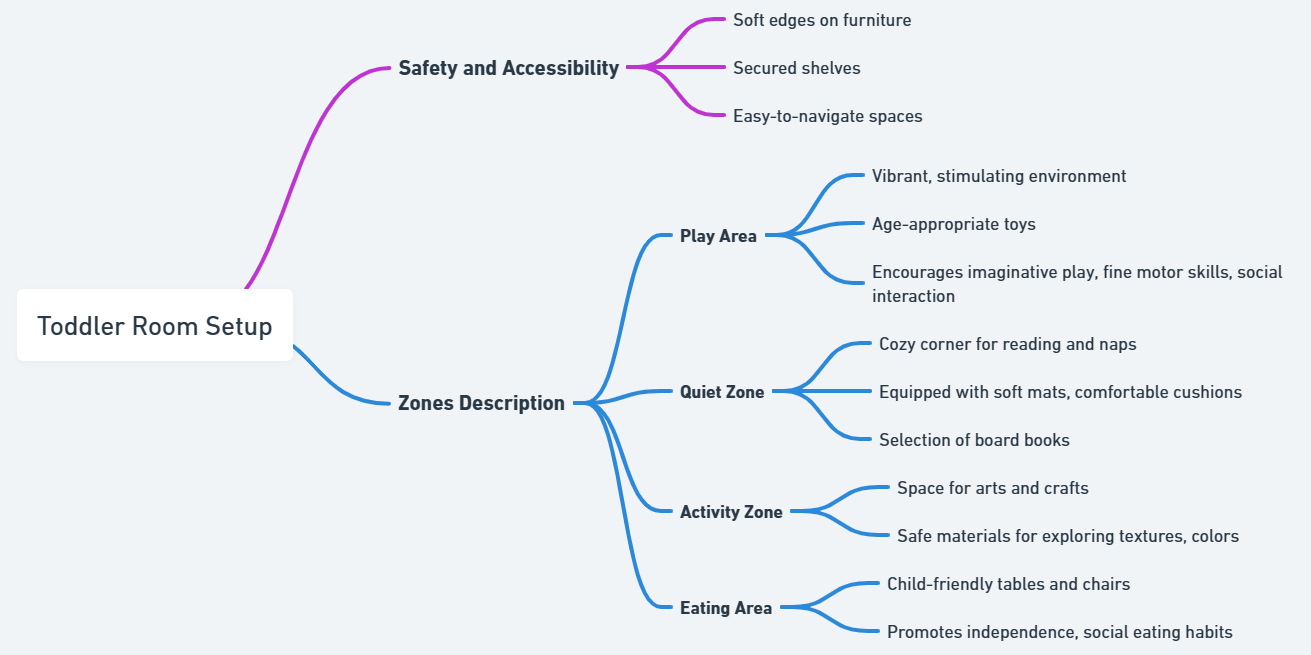

Setup an educational setting that responds to the developmental needs of a toddler would be key to guiding toddlers in their learning and development. Security measures such as cushion edges in furniture, secured storage shelves, and wide room for movement will also be important. The space would be divided into separate zones: a play area with toys and activities suitable for the age group, a comfy quiet zone for reading and nap time, an area for arts and crafts, and a separate area with kids (Pierucci et al. 35-43).

Toys that stimulate imagination, fine motor skills, and socialization should be provided in the play area. The quiet zone is meant to be a zone for recreation and literacy development. The activity zone must be safe for exploring different textures and colours to promote creativity (Pierucci et al. 35-43). The environment for the dining area should enable the promotion of social eating habits and independence.

To successfully reach the objective of providing a conducive learning environment, it is important to analyse the needs of toddlers (Holla et al., 2079-2086). Parenting style, child characteristics, and the home environment are the potent factors that have been proven to influence the developmental context of toddlers (Song et al. 2354-2364; Hoyt et al. 168-175). Besides this, evaluation of children’s early development through periodical visits is an important sign for early identification of the areas of concern (Baillargeon 62-68).

Figure 1 Comprehensive Toddler Room Layout and Design (Source: Self-Created)

Selection of Toys and Materials

Toys for toddlers should be evaluated based on developmental appropriateness, safety, and capacity to induce the learning process. For example, construction kits can enhance the fine motor skills required for hand-eye coordination and space awareness (Garon et al. 31-60). Playing with dolls allows toddlers to imagine different situations and develop empathy and social skills through pretend play (Dawson et al., e17-e23). Furthermore, sensory bins filled with items such as rice or sand offer the chance for tactile involvement, stimulating the senses and contributing to cognitive improvement (Campbell 113-149).

Studies show that children’s toy choices are based on a combination of their tastes and those of peers, thus demonstrating a social dimension to toy selection (Kanagasabai et al. 1147-1162). Additionally, the social environment during play affects the duration of sustained attention episodes in children (Shic et al. 246-254). When it comes to children’s preferences for toys, including gender-typed preferences, this information will help caregivers select toys that match children’s interests and the developmental needs of the kids (Ray et al. 43-57). Toys are among the most important aspects of a toddler’s development because they affect the child’s cognitive, social, and emotional development.

Reflection

When designing a toddler room that complies with developmentally appropriate practice, a careful and research-backed approach is needed. Each step, from creating the layout to selecting zones, toys, and materials, worked toward promoting an environment that allows for comprehensive toddler development. It was a priority to ensure that the structure meets each child’s physical, cognitive, emotional, and social needs, creating a safe, stimulating, and nurturing space for development and learning.

Planning of the toddler room was integrated with the research. By applying the theory of education and research studies into child development (Brewer et al.; Toombs et al., 87-91; Yoshida and Smith 229-248), the decisions are grounded on research-based practices, which makes an area that does not just meet toddler’s immediate needs but also is formulating a platform for life-long learning. Research shows that early education and proper techniques greatly impact children’s cognitive processes in their growing-up years, and it emphasizes the need for an environment that supports their initial learning experiences (Brewer et al.; Campbell 113-149).

The toddler room’s design has considered the different aspects of the child’s development and has designated areas that support each aspect. As one example, the playground was intended to develop the areas of imaginative play, fine motor skills, and social interaction (Brewer et al.). A sofa for reading was a cozy spot that enhanced book reading and mental well-being (87-91). Activity zones were responsible for sensory exploration that provided creative opportunities and the use of safe materials (Yoshida and Smith 229-248). Additionally, the dining area is designed to encourage independence, social eating habits, and physical and social development (Campbell 113-149).

The toys and materials selected aligned with the ideas that included developmental appropriateness, safety, and the ability to create learning through play. Toys such as blocks were selected to improve fine motor skills and spatial intelligence (Andreadakis et al. 297-314). The dolls were a tool to help develop empathy and social skills through make-believe scenarios. Sensory bins with rice and sand were prepped to encourage tactile exploration and cognitive development. By choosing toys that meet developmental goals and follow safety standards, the toddler room was stocked to accommodate individual children’s needs to enhance their overall development.

Finally, creating the toddler room was a thoughtful and research-based exercise that embraced developmentally appropriate practices. Through the application of research, careful planning, and a spotlight on children’s wholeness, the toddler room became an environment beneficial for physical, mental, emotional, and social development and with great possibilities for learning.

Part 2: Daily Schedule Inclusion

Developmentally Appropriate Daily Schedule

Table 1: Daily Schedule for Toddlers

| Activity | Time Allocation | Description |

| Morning Welcome | 30 minutes | Begin with a gentle transition from home to the classroom environment. Activities include free play with soft toys and puzzles, facilitating a smooth adjustment to the day ahead. |

| Circle Time | 15 minutes | This is a short, interactive session focusing on songs, simple stories, and basic greetings. It promotes language development and social interaction and recognizes the limited attention span of toddlers. |

| Exploratory Play | 45 minutes | Children engage in unstructured play in different zones of the room. This period supports cognitive and physical development through self-directed exploration of materials and space. |

| Snack Time | 20 minutes | This is a structured yet social time where children learn about hygiene, practice self-feeding, and engage in quiet conversations. It fosters independence and social skills. |

| Outdoor Play | 30 minutes | Weather permitting, outdoor activities provide opportunities for gross motor skill development, nature exploration, and sensory play. |

| Art and Sensory Activiities | 30 minutes | Guided activities allow toddlers to explore textures, colors, and creative expression. Materials are safe, non-toxic, and suited to their developmental stage. |

| Lunch and Quiet Time | 60 minutes | Following lunch, a designated quiet time allows for rest or napping, catering to individual sleep needs and promoting emotional regulation. |

| Afternoon Exploration | 45 minutes | This was a repeat of the exploratory play session from the morning, offering children a chance to engage with different materials or continue activities they enjoyed earlier. |

| Story Time | 15 minutes | This is a calm, engaging activity to wind down the day. It focuses on picture books and simple storytelling to stimulate imagination and language skills. |

| Farewell Circle | 15 minutes | End the day with a short circle time, including songs and a review of the day’s activities, reinforcing routines and providing closure. |

Reflection

The toddler schedule is carefully designed to provide well-rounded development across physical, mental, emotional, and social domains. All activities are specifically designed to address the traits and necessities of toddlers at every period of the schedule.

The Importance of Routine

The predictability inherent in the daily routine, with the frequent occurrence of circle time, snack time, and story time, gives the toddlers a feeling of safety and familiarity desired for their emotional development Campbell. Research points out how important routines are in early childhood settings in developing a sense of safety and belonging among kids (Zhang et al. 2021:1805-1813). Caregivers help toddlers manage their emotional well-being by acquiring the necessary day-to-day elements that provide a stable and secure environment.

Balancing Activities

The schedule builds a thoughtful balance between busy and quiet segments that reflect the different dynamics of toddlers; they get tired and distracted at different times. Outdoor and exploratory play sessions are venues for physical exertion and cognitive stimulation. At the same time, quiet time and Storytime provide essential moments for relaxation and restoration, which are important for the child’s overall well-being, according to the study of Kelliher and Anderson (83-106). This equilibrium will give toddlers the engagement and the relaxation they need for optimum development.

Inclusion of Exploratory and Sensory Activities

The constant exposure to other people’s opinions and biases can profoundly affect an individual’s belief system. The inclusion of sensory and active learning sessions within the schedule is based on toddlers learning more effectively by doing things themselves (Yung et al.). Activities promoting tactile exploration, creative expression, and cognitive stimulation promote curiosity and support toddlers’ cognitive, language, and sensory-motor development (Szymlek‐Gay et al., 2020, pp. 244-250). Different materials and textures can be introduced to toddlers to sharpen their sensory processing and improve their cognitive skills.

Social and Emotional Growth

Group games and meals are specially created to improve toddlers’ social skills and emotional regulation (Luyster et al. 1305-1320). These experiences help toddlers learn how to communicate, cooperate, and develop empathy in a safe and controlled environment, thus promoting the establishment of necessary social skills. Just as toddlers learn to navigate social interactions, express their emotions, and build peer relationships in group settings, they also lay a foundation for healthy social development.

Reflection and Flexibility

The daily schedule not only offers a framework for the day but also leaves room for the individual interests and needs of the child to be addressed (Byeon & Hong e0120663). This adaptability is key to creating an environment where learning is nourished, and learners’ individual qualities and preferences are respected. By attending to the children’s cues and adapting activities as required, caregivers can create an interactive and all-encompassing room where each child is being supported in their developmental progress (Ray-Subramanian et al. 679-684).

Ultimately, the day schedule for toddlers leads to a comprehensive and thoughtful approach to meeting their developmental needs. The schedule will include regular elements, balanced with physical and sensory experiences, social and emotional growth, and some flexibility, allowing caretakers to adjust the schedule and support the holistic development of toddlers. Thoughtful planning and incorporation of research-proven techniques will establish a solid ground for the preschoolers’ growth, learning, and wellness.

Part 3: Learning Environment Reflection

In the first years of a child’s life, a learning environment directly influences the establishment of the child’s developmental routes. Toddlers’ surroundings are not just places where they learn but an integral part of learning. The remaining section of the paper describes the design of a toddler room that uses the concepts of developmentally appropriate practice (DAP) to enhance toddlers’ physical, cognitive, emotional, and social development.

Physical Environment: Safety, Accessibility, and Engagement

The toddler room’s physical environment is purposefully designed so that safety, accessibility, and engagement are the primary considerations in creating a place that aids discovery and learning. All the information was studied and changed accordingly to reflect the toddler’s core development process and ensure that this space will become a warm and interesting development area for them. Safety was the most critical concern in designing the toddler room’s physical space. All the furnishings and materials were carefully chosen with a close view of details to remove hazards and create a safe space for toddlers to explore without fear of being hurt. Removing anything harmful within the room allows the carers to create a secure environment where the toddlers grow in self-esteem and independence as they move and interrelate within the space.

Another significant factor in the design of the surroundings was the availability issue. The materials were arranged low enough so the toddlers could reach them independently, encouraging self-motivated learning. Caregivers place objects within reach of toddlers, allowing them to make choices, discover their interests, and participate in activities that will facilitate their cognitive and physical growth. This purposeful layout promotes autonomy and gives toddlers agency, which actively encourages them to be involved in their learning (Bird 166-176).

The play zones of the room were laid out to appear attractive and exciting for the children. The layout provided convenient transitions between each zone – the reading corner, art station, and the sensory play area, which made it possible for toddlers to walk around and join in the games that attracted their attention. Combining natural lighting with plants and nature-inspired elements was a carefully crafted plan to achieve a warm and cozy ambiance. Studies have proved that exposure to natural settings boosts the well-being and creativity of toddlers, making it appropriate for such an area in the overall development of the children (Nolan and McBride 594-608).

Activity Inclusion: Balancing Structure with Flexibility

During the design process of the toddler learning area, we have tried to balance the planned learning activities and kids’ free play. Such balance was thoughtfully designed to provide for toddlers’ diverse developmental stages and needs. Structured activities like circle time and guided art projects were precisely designed to foster information and skills in a caring and interactive environment. On the other hand, ample time for free play was one of the methods of encouraging creativity, problem-solving, and social interaction among peers, providing a holistic learning and development approach.

Purposefully designed group activities like circle time and art projects for the children in the toddler room were uniquely crafted to allow the little ones to participate actively in meaningful learning experiences. For example, circle time allowed for social interaction, language development, and familiarization with new concepts such as songs, stories, and group activities. Chen & Li’s guided art projects promoted creativity, being a doorway for developing fine motor skills, self-expression, and cognitive abilities (Barbaro and Dissanayake 830-840). The structured activities were incorporated daily into the care plans by the caregivers to create an ecosystem that fosters the growth and development of toddlers.

The time set aside for free play was a lot and gave the toddlers ample opportunity to explore, make, and interact with their environment without the supervision of an adult. Free play is an indispensable element in developing creative, problem-solving, and socializing abilities among peers (Luyster et al. 1305-1320). In free play, toddlers can involve themselves in various imaginative sceneries, try out different materials, and enhance their social skills in a relatively unordered fashion. This equilibrium of structured games and free play will allow toddlers to develop at their own pace, discover their interests, and demonstrate their inner selves through direct interaction with their environment.

Multimodal sensory experiences for toddlers were our main focus when choosing the materials for the different activities. This activity was meant to trigger multiple senses by using art supplies with different textures and musical instruments to help with cognitive development and integration of the senses (Bannerman et al., 79-89). The studies reveal that early in childhood, multisensory experiences are very important for successful learning, memory retention, and sensory development (Brodsky and Sulkin 330-339). Caregivers can add different sense engagement materials to develop activities that are informative and fun and learning for toddlers, who are very curious by nature.

Goals for Holistic Development

The main objective was to foster an environment conducive to toddlers’ cognitive, physical, emotional, and overall development. The setting had to be finely tuned so toddlers could be visible, listened to, and felt important. It had to guarantee both individual exploration and group interaction, as well as belongingness and engagement, what people feel in that space. As for the toddler program, the aim was to develop social-emotional skills through shared activities that necessitated teamwork, sharing, and empathy (Schuhmacher & Kärtner). Through cooperation, toddlers can acquire the necessary social skills, like communicating, collaborating, and emotional regulation. The room’s design helped the kids communicate among themselves, enabling social interactions and eventually a foundation for community building. Moreover, the shelter’s cozy nooks provided private moments of solitude or quiet play, promoting emotional well-being and enabling opportunities for self-reflection and relaxation (Hvit 311-330).

All of the toddlers’ rooms had activities that challenged the development of the toddlers’ problem-solving skills and motor abilities in a safe and supportive environment (Quiñones et al. 25-33). Through participation in various activities that tease cognition, toddlers were exposed to several new concepts, developed their critical thinking capacity, and advanced their knowledge base. The choice of materials to create a multisensory environment was designed to engage multiple senses, ensuring cognitive development and sensory integration (Hess et al. 132-138). Through hands-on experimental means and by presenting them with interactive play, toddlers can enrich their cognitive abilities, improve their fine and gross motor skills, and learn through experiences tailored to their development.

During the planning process of the activity schedule and material selection, it was key to design engaging and exciting experiences that were interesting and relevant to the natural curiosity of toddlers. Caregivers did this by combining planned learning activities and free play for toddlers so that they could grow, learn and enjoy in an environment that supports all round development. The special layout of the activities and materials created a dynamic and stimulating environment that supported toddlers’ cognitive, physical, emotional, and social growth, fostering a varied approach to learning and development.

Conclusion

Considering the comprehensive model of designing a toddler-friendly environment, this report highlights that proper planning is very important in early childhood education. Through the emphasis on developmental appropriateness, safety, and exploratory learning, it lays out the groundwork for producing all-rounded individuals, which underlines the crucial part educators play in shaping the future of young learners.

Work Cited

Andreadakis, Eftichia, et al. “How to support toddlers’ autonomy: socialization practices reported by parents.” Early Education and Development, vol. 30, no. 3, 2018, p. 297–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2018.1548811

Baillargeon, Raymond, et al. “Clinical practice guidelines for monitoring children’s behavioral development at the 18‐month well‐baby visit: a decision analysis comparing the expected benefit of two alternative strategies”. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, vol. 27, no. 1, 2020, p. 62–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.13385

Bannerman, Diane, et al. “Balancing the right to habilitation with the right to personal liberties: the rights of people with developmental disabilities to eat too many doughnuts and take a nap.” Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, vol. 23, no. 1, 1990, p. 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1990.23-79

Barbaro, Josephine, et al. “Diagnostic stability of autism spectrum disorder in toddlers prospectively identified in a community-based setting: behavioural characteristics and predictors of change over time”. Autism, vol. 21, no. 7, 2016, p. 830-840. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361316654084

Bird, Jo, et al. ““you need a phone and camera in your bag before you go out!”: children’s play with imaginative technologies”. British Journal of Educational Technology, vol. 51, no. 1, 2019, p. 166-176. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12791

Brewer, Neil, et al. “Autism screening in early childhood: discriminating autism from other developmental concerns”. Frontiers in Neurology, vol. 11, 2020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.594381

Brodsky, Warren, et al. “What babies, infants, and toddlers hear on fox/disney babytv: an exploratory study.”. Psychology of Popular Media, vol. 10, no. 3, 2021, p. 330-339. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000321

Byeon, Haewon, et al. “Relationship between television viewing and language delay in toddlers: evidence from a korea national cross-sectional survey”. Plos One, vol. 10, no. 3, 2015, p. e0120663. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0120663

Campbell, Susan, et al. “Behavior problems in preschool children: a review of recent research”. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, vol. 36, no. 1, 1995, p. 113-149. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb01657.x

Chen, Jennifer, et al. “Developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood education”., 2022, p. 53-76. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003274865-4

Dawson, Geraldine, et al. “Randomized, controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: the early start denver model”. Pediatrics, vol. 125, no. 1, 2010, p. e17-e23. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-0958

Garon, Nancy, et al. “Executive function in preschoolers: a review using an integrative framework.”. Psychological Bulletin, vol. 134, no. 1, 2008, p. 31-60. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.31

Hess, Darlene, et al. “Holistic nurses and the new mexico board of nursing”. Journal of Holistic Nursing, vol. 24, no. 2, 2006, p. 132-138. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898010105282577

Holla, Chaithra, et al. “Parenting toddlers: evidences of parental needs from south india”. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, vol. 69, no. 8, 2023, p. 2079-2086. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207640231188032

Hoyt, Catherine, et al. “Developmental delay in infants and toddlers with sickle cell disease: a systematic review”. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, vol. 64, no. 2, 2021, p. 168-175. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.15048

Hvit, Sara, et al. “Literacy events in toddler groups: preschool educators’ talk about their work with literacy among toddlers”. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, vol. 15, no. 3, 2014, p. 311-330. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798414526427

Kanagasabai, Parimala, et al. “Association between motor functioning and leisure participation of children with physical disability: an integrative review”. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, vol. 56, no. 12, 2014, p. 1147-1162. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.12570

Kelliher, Clare, et al. “Doing more with less? flexible working practices and the intensification of work”. Human Relations, vol. 63, no. 1, 2009, p. 83-106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709349199

Lee, A-Young, et al. “Improving children’s emotional health through installing biowalls in classrooms”. Journal of People Plants and Environment, vol. 24, no. 1, 2021, p. 29-38. https://doi.org/10.11628/ksppe.2021.24.1.29

Luyster, Rhiannon, et al. “The autism diagnostic observation schedule—toddler module: a new module of a standardized diagnostic measure for autism spectrum disorders”. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, vol. 39, no. 9, 2009, p. 1305-1320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-009-0746-z

Nolan, Jason, et al. “Beyond gamification: reconceptualizing game-based learning in early childhood environments”. Information Communication & Society, vol. 17, no. 5, 2013, p. 594-608. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2013.808365

Orchard, Kimberly, et al. “”we’re all friends here”: how do early childhood educators promote friendship in the classroom?”., 2023. https://doi.org/10.32920/ryerson.14660316

Pierucci, Jillian, et al. “Play assessments and developmental skills in young children with autism spectrum disorders”. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, vol. 30, no. 1, 2014, p. 35-43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357614539837

Quiñones, Gloria, et al. “Collaborative forum: an affective space for infant–toddler educators’ collective reflections”. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, vol. 43, no. 3, 2018, p. 25-33. https://doi.org/10.23965/ajec.43.3.03

Ray, Dee, et al. “Use of toys in child-centered play therapy.”. International Journal of Play Therapy, vol. 22, no. 1, 2013, p. 43-57. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031430

Ray-Subramanian, Corey, et al. “Brief report: adaptive behavior and cognitive skills for toddlers on the autism spectrum”. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, vol. 41, no. 5, 2010, p. 679-684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-1083-y

Schuhmacher, Nils, et al. “Explaining interindividual differences in toddlers’ collaboration with unfamiliar peers: individual, dyadic, and social factors”. Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 6, 2015. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00493

Shic, Frederick, et al. “Limited activity monitoring in toddlers with autism spectrum disorder”. Brain Research, vol. 1380, 2011, p. 246-254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2010.11.074

Song, Jae, et al. “Positive parenting moderates the association between temperament and self-regulation in low-income toddlers”. Journal of Child and Family Studies, vol. 27, no. 7, 2018, p. 2354-2364. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1066-8

Szymlek‐Gay, Ewa, et al. “Quantities of foods consumed by 12‐ to 24‐month‐old new zealand children”. Nutrition & Dietetics, vol. 67, no. 4, 2010, p. 244-250. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-0080.2010.01471.x

Toombs, Courtney, et al. “Safe spine surgery during the covid-19 pandemic”. Clinical Spine Surgery a Spine Publication, vol. 34, no. 3, 2020, p. 87-91. https://doi.org/10.1097/bsd.0000000000001084

Yoshida, Hanako, et al. “What’s in view for toddlers? using a head camera to study visual experience”. Infancy, vol. 13, no. 3, 2008, p. 229-248. https://doi.org/10.1080/15250000802004437

Yung, Daniel, et al. “Labor planning and shift scheduling in retail stores using customer traffic data”. SSRN Electronic Journal, 2020. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3695353

Zhang, Xiaochun, et al. “Nursing scheduling mode and experience from the medical teams in aiding hubei province during the covid-19 outbreak: a systematic scoping review of 17

studies”. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, vol. Volume 14, 2021, p. 1805-1813. https://doi.org/10.2147/rmhp.s302156

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Academic Master Education Team is a group of academic editors and subject specialists responsible for producing structured, research-backed essays across multiple disciplines. Each article is developed following Academic Master’s Editorial Policy and supported by credible academic references. The team ensures clarity, citation accuracy, and adherence to ethical academic writing standards

Content reviewed under Academic Master Editorial Policy.

- Editorial Staff